A quick Q and A with Viktor Moskalenko

Viktor Moskalenko is one of the leading chess instructors of our time. Among the books he wrote for New In Chess are Revolutionize Your Chess, Training with Moska, and numerous inspiring opening manuals such as The Fully-Fledged French, The Wonderful Winawer and The Fabulous Budapest Gambit.

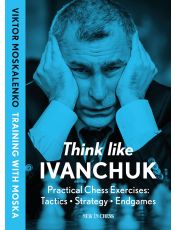

Moskalenko’s latest book is Think Like Ivanchuk, a training manual based on the games of Vasyl Ivanchuk, one of the strongest players in history not to become World Champion. The incredible talent and chess strength of Ivanchuk is on show all through the book as Moskalenko investigates ‘Chuky’s’ direct encounters with the world champions and his most brilliant contemporaries. The author argues that ‘for the period of the early 1990s to the near-present, the strongest chess player in the world was Vasyl Ivanchuk – if he was in good shape!

A bold statement that is hard to argue with if you look at Ivanchuk’s many wins against the leading players in the period described.

Viktor Moskalenko was Ukrainian champion in 1987 and won many international tournaments. He has known Ivanchuk for more than forty years and has worked for him as a second.

To give the reader a better idea of the background of ‘Moska’s’ new book, I invited him to a quick Q and A.

When was the first time you met Vasyl Ivanchuk and what was it that led to your friendship despite the age difference?

‘It happened in the capital of Ukraine, Kyiv, in 1977, when I was seventeen and Ivanchuk was eight. Since I had only started studying chess at the late age of fifteen, we had in common that this was one of our first chess trips away from home. The youth championship of the ‘Avangard Society’ was taking place there and despite our little experience, we both performed successfully. Vasyl won the U-10 category, and I won the main tournament.

The U-10 games usually ended very quickly, but Vasyl did not leave the hall and stayed to watch the games of the older players, particularly those on the leader boards.

When everything was finished we would walk back from the playing hall to the hotel and enthusiastically discuss what had happened. That's how we became friends.

I remember that on one of these walks I ‘secretly’ confessed to Vasya (as I have called him all my life) that the next day I was going to play the King's Gambit with White. He replied: ‘Wow, but this romantic opening can be risky, because it was played a hundred years ago!’ I assured him that I would crush my opponent and that’s exactly what happened the next day as my gambit attack led to a quick victory. Vasya was delighted!

What was it that was special about his talent compared to other gifted youngsters?

‘Already in Kyiv, Vasyl had several important distinguishing features. He was a very kind boy with blue eyes full of light, he was inquisitive and educated, with great respect for others, especially for those who understood chess better than he did. As became more clear by the year, his chess talent is based on a unique combination of imagination and memory. Thanks to these natural gifts, he created within himself the now famous 'Planet Ivanchuk'. Even as a child, his level of internal vision of the chessboard and his flawless and unerring calculation of variations were very impressive.

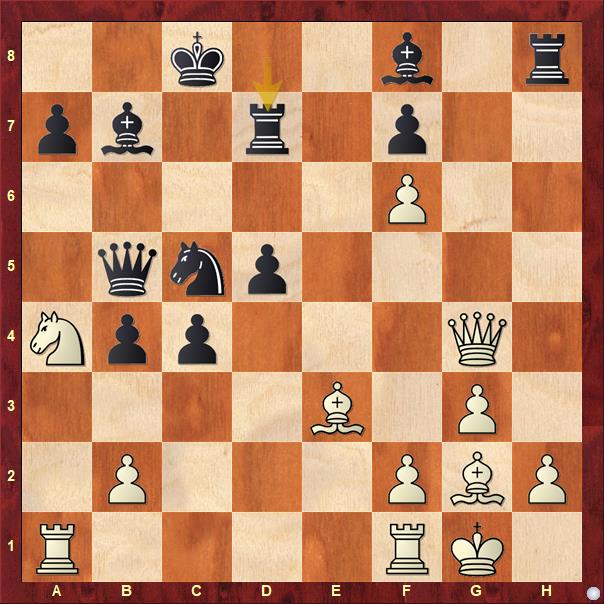

If you’re looking for examples, you can have a look at his spectacular queen sacrifice against Shirov in Wijk aan Zee in 1996. Ivanchuk-Shirov

Ivanchuk-Shirov

Wijk aan Zee 1996

position after 20…Rd7

Here he played: 21.Qg7!!

A fascinating sacrifice and one of the most brilliant moves in modern chess practice! This queen sacrifice for two minor pieces does not lead to a quick win, but gives White a lasting initiative. Black’s king will be a target for White’s active pieces. Surprisingly, Vasyl found this paradoxical move at the board. The chess world was no less impressed by this sacrifice than Alexey Shirov, who would have loved to have found this idea himself! White won on move 35.

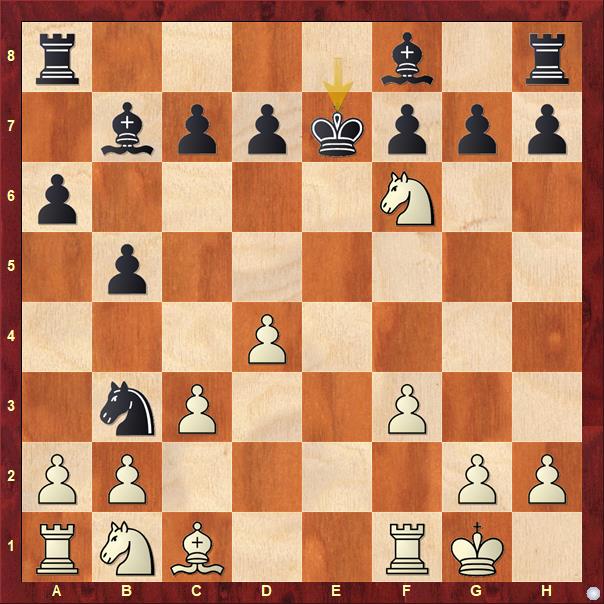

And there’s another brilliant queen sacrifice that he uncorked in a rapid game in the Amber tournament in Nice in 2008 against Karjakin. Ivanchuk-Karjakin

Ivanchuk-Karjakin

Amber Rapid, Nice 2008

Position after 13…Nc6

The move Ivanchuk discovered here is baffling and has no analogies in modern chess: 14.Qxe6+!!?

A purely positional sacrifice of the queen for just two pawns! Ivanchuk revealed that he had prepared this novelty in the short period between the Linares tournament of 2008 and his next event, the annual Amber blindfold and rapid tournament.

‘Using a computer in the creative process lowers the artistic quality,’ wrote Viktor Korchnoi. Still, only a genius like Ivanchuk can come up with such imaginative finds. White won on move 49.

Ivanchuk’s rise to the world top was quick. Did you think he was destined to be world champion?

‘The first to express this thought was the famous grandmaster Josif Dorfman, one of Garry Kasparov's seconds in his first four matches for the world championship against Anatoly Karpov. It was in 1988, at a strong international tournament in Lviv, where Ivanchuk was just beginning his rise and shared 2nd to 4th place with Vladimir Malaniuk and myself. Dorfman put it like this: ‘Ivanchuk is a future world champion; he already knows much more than any chess player and sees everything at the board.’ At that point, considering Ivanchuk's age and talent, I agreed with him 100 per cent!’

As you also mention in your book: On a good day he could (and can) defeat anyone. What stopped him from winning the highest title?

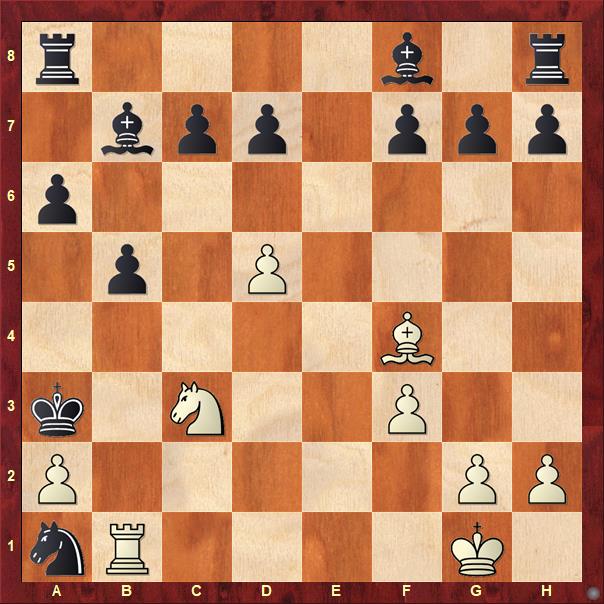

‘Ivanchuk has a strong creative spirit; he is more of an artist than a conqueror, with all that this implies. There’s this most remarkable story about his game against Beliavsky in the Linares tournament of 1992. I heard the story from Felix Levin, a grandmaster who used to live in Lviv and who was Ivanchuk’s second in those years. At the time Ivanchuk knew the important theoretical sources like the Informant and the New In Chess Yearbooks by heart. Before the game with Beliavsky, he and Felix had analyzed a crucial idea that was overlooked in Informant 52 and found how White could get a big advantage in a variation of the Ruy Lopez. After the game had started, Felix, who was in the press room, was pleasantly surprised to see the position they had investigated appear on one of the monitors. Ivanchuk-Beliavsky

Ivanchuk-Beliavsky

Linares 1992, Round 6

Position after 13…Ke7

Here Ivanchuk thought for a long time and Felix Levin almost fell from his chair when after this long think, Vasyl simply captured the knight on b3. 14.axb3

The move Felix had expected to see was the novelty they had prepared: 14.Bg5! Nxa1 (14...gxf6 is met by 15.Re1+) 15.Re1+ Kd6 16.Bf4+ Kc6 17.d5+ Kc5 with a winning position for Black according to Patrick Wolff in Informant 52. However, as Ivanchuk had found, after 18.b4+! Kc4 19.Na3+ Kxc3 20.Ne4+ Kxb4 21.Rb1+ Kxa3 22.Nc3

it is White who wins as Black cannot stop the mating threat Bc1 mate. All this had been prepared by Ivanchuk, but to Levin’s utter amazement he decided differently and after 14...Kxf6 the position was equal and the game ended in a draw on move 62.

After the game, a perplexed Felix asked: ‘Vasyl, what the hell happened, why didn’t you play the prepared 14.Bg5!!?’

And the answer was: ‘That was too easy. I felt like playing and defeating Beliavsky at the board. It wouldn't have been me, and I would have lost a day to play a game.’

‘What to say? Ivanchuk brought magical beauty to chess and developed an extraordinary imagination. But with this artistic character, he was not able to ‘conquer the chess world’, to be ambitious, aggressive and destructive. With those elements missing, it was not possible to obtain the highest title. Some external factors also had an impact, such as the rapidly intensifying rivalry from a strong generation and the tough and divided world championship after Kasparov's split from FIDE in 1993.

Another significant factor was the advent of the computer. Ivanchuk lost the clear advantage of his invaluable and personally accumulated knowledge when the chess engines equalized everyone!’

‘Nevertheless, Vasyl dreamed of winning the world title in classical chess more than once. In 1991, in the Candidates Matches, he was unexpectedly stopped by Artur Yusupov. And in 2002, he dramatically lost the final match for the title to Ruslan Ponomariov.

In this light, it is worth adding that he did become world champion in blitz and rapid chess, in Moscow in 2007, and in Doha in 2016, respectively.’

For some time in his younger years he worked with Anatoly Karpov. What do you believe he learned from him?

‘Well, as far as I know, it wasn't exactly a standard collaborative creative effort. There was, and still is, a chess manager in Moscow called Alexander Bakh. Thanks to him, for example, my training with Ivanchuk was organized in 1993, and later also a training match with Alexander Morozevich in 1994. Years before these events, Bakh organized meetings between Karpov and Ivanchuk, as he was a member of the team of the former world champion. At these session, which usually took place in resorts, wine was drunk and countless blitz games were played… What he learned there is hard to say, but at the very least it helped Vasyl become one of the best blitz players in the world! I describe various aspects of his relationship with Karpov in more detail in the book.’

Probably his greatest ‘inspiration’ was Kasparov, who he saw as a touchstone, as the best he could beat. Often he focused so much on this one game against Kasparov in a tournament that he was less motivated in the other games.

‘It was only natural. In the early ‘90s Ivanchuk felt his chess superiority after convincing victories in tournaments such as Linares 1991 and others. He reached second place in the FIDE world ranking. So it was logical that his main target became the world champion, Garry Kasparov. However, in addition to his enormous strength and other advantages, Kasparov also had the best team.

Under such circumstances, the only option Ivanchuk had was maximum concentration for each game against the world champion. As we know, he was able to even the odds and scored four brilliant wins against Kasparov. However, in a broader sense he had little chance of individually defeating such a powerful machine. After the Bobby Fischer era, chess preparation became dominated by teams and was later further enhanced by computers.’

To what extent does he still live ‘in chess’? Is it a passion that keeps him fully fascinated till this day?

‘Vasyl has stated that his only, irreplaceable love is chess. I am sure that he still has a huge reserve of unrealized ideas in chess. And such treasures are never thrown away.’

When did his interest in checkers arise and how do you explain his fascination for this game? Everyone remembers the prize-giving of the World Rapid Championship in 2016, when he interrupted a game of checkers to pick up his gold medal only to immediately rush back after the prize-giving to finish that game against Baadur Jobava.

‘Somewhere in the early 2000s, Ivanchuk began to study and play checkers, as some sort of self-defence against the stress of chess. The main thing was that by devoting time to checkers, he took a break from chess.

In 2013, after his failure in the Candidates Tournament in London, his nervous system collapsed. Next he played poorly in the FIDE Grand Prix in Thessaloniki. And right after that, he had a match with mixed time controls against Anish Giri in Leon. Vasyl flew to Barcelona and we went to my house.

Upon seeing my computer, he immediately sat down and began playing checkers online, bullet. He also had books on checkers with him and the whole night we spent solving checkers combinations. The match lasted two days and on the first day he did very poorly. That evening beer and Spanish food worked wonders and he had a remarkable comeback in the blitz games on the second day. When he was asked about that miraculous turnaround after the match he said that he had already been thinking about quitting chess. Just like in life you can change your wife. But that chess was a unique love that you cannot change for anything! And he added that he had calmed down and forgot about all his difficulties and that a delicious glass of beer had greatly improved his mood.’

‘I can also tell you what happened at the World Cup in 2013 when in the fourth round he lost the match against Kramnik. Before losing the first game with White, instead of preparing, Vasyl had been playing checkers, online blitz, all day. So my conclusion would be that Ivanchuk’s interest in checkers turns into a passion when his nervous system requires a strong distraction.’

How long will he continue to play? Will he be a second Korchnoi, who played competitive chess almost till his last breath?

‘Oh yes, it might be something similar, because both of them are forever devoted to the game of chess. However, their reasons and motives are different. It is well known that for the legendary Viktor Korchnoi, chess was a real war with all its consequences. For Ivanchuk, chess is self-expression and a creative process. Of course, the result also matters, but in the appropriate balance. I know that for Vasya to be completely happy in a tournament, it is enough to play at least one beautiful game!’