Adult Improvement

These book reviews by Matthew Sadler were published in New In Chess magazine 2024#3

Books dedicated to adult improvement can have long-lasting value. Especially the human thought process around the moves (below elite level) hasn’t changed as much in the past thirty years as you would think.

by Matthew Sadler

We start this month’s reviews with some books dedicated to (adult) improvement, starting with Perpetual Chess Improvement by Ben Johnson (New In Chess). Over the last few years, Ben Johnson’s Perpetual Chess Podcast has become a haven for intelligent conversation about chess, covering a wide range of topics such as elite chess and chess books! One popular series within the podcast is dedicated to ‘Adult Improvers’, where amateurs with varied chess backgrounds explain how they train and try to improve. This series – running now since 2017 – was the inspiration for Perpetual Chess Improvement, with 41 interviews providing a host of tips, tricks and discussion material!

We start this month’s reviews with some books dedicated to (adult) improvement, starting with Perpetual Chess Improvement by Ben Johnson (New In Chess). Over the last few years, Ben Johnson’s Perpetual Chess Podcast has become a haven for intelligent conversation about chess, covering a wide range of topics such as elite chess and chess books! One popular series within the podcast is dedicated to ‘Adult Improvers’, where amateurs with varied chess backgrounds explain how they train and try to improve. This series – running now since 2017 – was the inspiration for Perpetual Chess Improvement, with 41 interviews providing a host of tips, tricks and discussion material!

The book is divided into four parts. Part 1 defines the ‘Pillars of Chess Improvement’, which are essentially four forms of chess work that most or all interviewees agree are essential. These are: playing serious games, reviewing them, doing tactics and finding a community. Part 2 dives into more contentious topics – such as studying openings or not – on which many different opinions exist! Part 3 examines how to approach the game away from the board such as setting a tournament routine. And finally Part 4 gives a quick overview of useful chess tools and how to use them.

This is simply a very good book, with so much advice and discussion that every player will find something of value, while the friendly and positive writing leaves you with a good feeling whenever you dip into it!

For example, one adult improver called Kare Kristensen managed to achieve the International Master title at the age of 54, having returned to chess in 2007 at the age of 42 after a decade-plus break from chess. The inevitable struggles are certainly not hidden away: ‘One thing that was very disappointing for me. After I played quite well for some time in 2008, I suddenly played extremely badly and I lost rating every time I played. And I was just below 2200 FIDE rating at a point around 2008. I remember I was writing an email to the chairman of my chess club and saying: Well I think I’d better stop because I can’t stand playing this badly. And I’ve been training. I’ve been doing all the right things which are supposed to be good for you, but just going totally downhill and making horrible mistakes all the time.’ I guess most chess players know how that feels.

The story ended well, however, and I really liked Kare’s summary of his whole experience: ‘In assessing your improvement, a key question to ask is: ‘Can I, and do I now play games which I wasn’t capable of before I resumed seriously working on my chess? ’And I am proud to say that the answer is yes!’

I read the book during a business trip abroad and while enduring a long delay in the train, I challenged myself with the question of whether anything was missing from the book. For all the wealth of insight and advice, was there a subject that hadn’t cropped up or had only been lightly touched upon?

I read the book during a business trip abroad and while enduring a long delay in the train, I challenged myself with the question of whether anything was missing from the book. For all the wealth of insight and advice, was there a subject that hadn’t cropped up or had only been lightly touched upon?

From my point of view and obsessions I decided that while tactical training is heavily recommended, intuition training hasn’t made it into the general consciousness yet. By intuition training, I mean training yourself to instinctively home in on good moves (ideally the best three or four moves) at first glance when encountering a position. This ability is partially implicit in the process of working at chess – get stronger and you’ll see better moves – but I think it’s a fundamental skill that deserves specific attention and training.

The reasoning is that the first moves that you see in a position shape and direct your thinking in a practical game. Those first thoughts are your entry point as you start digging into the position and you really want to start digging in the right place! I’ve been trying some training where I compare my initial ideas on a random position (after about 30 seconds to a minute’s thought) with the top-3 moves of the Leela engine with limited calculation (something like 100 halfmoves, which equates to a Leela strength of about 3000 Elo). So far, it seems quite promising!

All-in-all a valuable addition to the learning resources available for keen improvers! Somewhere between four and five stars for me, but I’ll take the first emergence of the English sun this year as a sign to bump it up to five!

Improve Your Chess Now by Jon Tisdall (New In Chess) is a reissue of the 1997 classic that attracted praise from amateur players and famous coaches alike! Its 238 pages are filled with advice, discussion, tips and tricks and exercises, and just like Perpetual Chess Improvement you can be pretty confident that every player will find something of interest and value in at least one of its sections.

Improve Your Chess Now by Jon Tisdall (New In Chess) is a reissue of the 1997 classic that attracted praise from amateur players and famous coaches alike! Its 238 pages are filled with advice, discussion, tips and tricks and exercises, and just like Perpetual Chess Improvement you can be pretty confident that every player will find something of interest and value in at least one of its sections.

I was quite surprised that the book had been republished without alterations, as most books written in the precomputer age tend to age quite poorly. However, I didn’t have that feeling at all when reading Improve Your Chess Now. I guess that’s because exact analysis is not the point of the book: it’s very much about the human thought process around the moves and – below the elite level – my experience is that this hasn’t changed as much in the past 30 years as you would think! The subjects are quite varied: Tisdall starts off with a critical appraisal of Kotov’s fabled ‘Tree of Analysis’, moves on to a chapter about the use of blindfold chess as a visualization aid and ends with a chapter of general advice and appendices of tactical themes. In fact I found Tisdall’s balanced critique of Kotov’s analytical method (detailed in the classic book Think Like a Grandmaster) to be the most interesting part of the book. Tisdall describes a natural ‘organic’ thinking approach in various positions quite evocatively and uses this to highlight the gaps in Kotov’s method and then gives advice to bridge those gaps. I did suddenly wonder though whether young players would get this reference. Are people still reading Kotov (as beginners of my era were ‘forced’ to!) or is everyone just practising calculation through bullet, blitz and puzzles?

The subjects are quite varied: Tisdall starts off with a critical appraisal of Kotov’s fabled ‘Tree of Analysis’, moves on to a chapter about the use of blindfold chess as a visualization aid and ends with a chapter of general advice and appendices of tactical themes. In fact I found Tisdall’s balanced critique of Kotov’s analytical method (detailed in the classic book Think Like a Grandmaster) to be the most interesting part of the book. Tisdall describes a natural ‘organic’ thinking approach in various positions quite evocatively and uses this to highlight the gaps in Kotov’s method and then gives advice to bridge those gaps. I did suddenly wonder though whether young players would get this reference. Are people still reading Kotov (as beginners of my era were ‘forced’ to!) or is everyone just practising calculation through bullet, blitz and puzzles?

A nice element of the book is that I wasn’t familiar with many of the games in it. A number of Jon’s best wins (and unfortunately, also some upsetting losses) are included and I very much liked the game Kunsztowicz-Keene Dortmund 1973, which Tisdall uses to demonstrate ingenious play in bad positions:

Uwe Wilhelm Kunsztowicz

Raymond Keene

Dortmund 1973

Queen’s Indian Defence

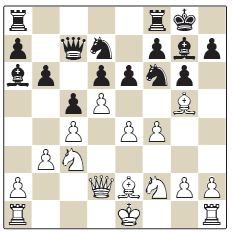

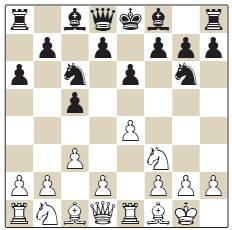

1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 b6 3.f3 c5 4.d5 g6 5.e4 d6 6.♘c3 ♗g7 7.♗g5 0-0 8.♕d2 ♘bd7 9.♘h3 ♘e5 10.♘f2 ♗a6 11.b3 ♕c7 12.♗e2 e6 13.f4 ♘ed7 Black’s Hypermodern play has not been too successful and White decides to hammer his advantage home by targeting the d6-pawn.

Black’s Hypermodern play has not been too successful and White decides to hammer his advantage home by targeting the d6-pawn.

14.dxe6 fxe6 15.♖d1 ♘b8

15...♘e8 16.♗g4 was rather painful, so Ray attempts to absorb White’s pressure in an ingenious manner. 16.♘b5

16.♘b5

16.♕xd6 ♕xd6 17.♖xd6 ♘e8 is the idea, hitting d6 and c3, when 18.♖d3 h6 wins back the f4-pawn, though the engines don’t think this is the end of the story at all after 19.♗g4, with the idea 19...hxg5 20.♗xe6+ ♔h7 21.♖h3+ ♗h6 22.fxg5.

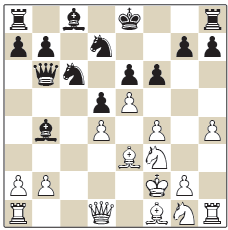

16...♗xb5 17.cxb5 ♘e8 18.♗c4 ♕d7 19.♘g4 ♗d4 20.h4 ♘g7 21.♘h6+ ♔h8 22.g4

White’s play reminds me of my blitz games at the moment! White is setting himself up for a huge assault. Somehow however, White doesn’t push things through, getting distracted as Black starts to nibble away at his position!

22...a6 23.♕e2 axb5 24.♗xb5 ♕a7 25.a4 ♘a6 The engines only want 26.♖xd4 followed by castling here, with a huge advantage though it feels very messy. White tries a solid build-up to keep control but ends up losing all momentum.

The engines only want 26.♖xd4 followed by castling here, with a huge advantage though it feels very messy. White tries a solid build-up to keep control but ends up losing all momentum.

26.♔f1 ♕b7 27.♗d3

27.♔g2 was still very good but White was obviously nervous about putting the king on the same diagonal as the black queen.

27...♘b4 28.♗b5 e5 Some time wasted from White, the king caught in the firing line on the way to safety and suddenly Black is OK!

Some time wasted from White, the king caught in the firing line on the way to safety and suddenly Black is OK!

29.h5 ♘e6

Now very much more than OK!

30.♔g2 ♘xg5 31.♖xd4 exf4 32.♕c4 cxd4 33.♕xd4+ ♕g7 34.♕xb4 ♕xh6 35.hxg6 f3+ 36.♔g3 ♕xg6 37.♗d3 ♖ae8 38.♖h5 ♕f6 39.♕d2 h6 0-1

A good book full of useful advice – definitely a good companion to Perpetual Chess Improvement! Four stars!

The first of Davorin Kuljasevic’s two books this month is The How To Study Chess On Your Own Workbook – Volume 2 (New In Chess).

The first of Davorin Kuljasevic’s two books this month is The How To Study Chess On Your Own Workbook – Volume 2 (New In Chess).

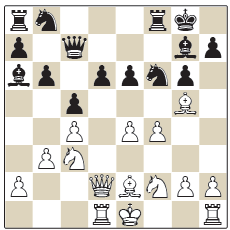

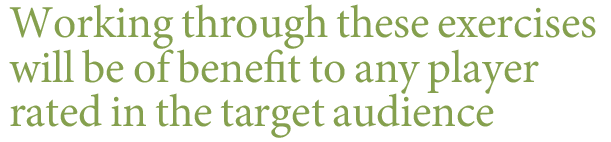

This 198-page book with an introductory chapter and four chapters of exercises actually fits very well with Ben’s and Jon’s books as it trains aspects of chess skill that both Ben and Jon note as very important – in particular visualization and tactics. On top of this there is some additional interesting middlegame training such as exchanging the right piece. One neat feature of the exercises is that Kuljasevic often gives a sequence of moves and then asks some questions about events within that sequence. It mirrors quite well the situation in a real game where you have to be alert at the right moment but you don’t know when that is! For example: ‘Find a hidden tactic in the following threemove sequence:

One neat feature of the exercises is that Kuljasevic often gives a sequence of moves and then asks some questions about events within that sequence. It mirrors quite well the situation in a real game where you have to be alert at the right moment but you don’t know when that is! For example: ‘Find a hidden tactic in the following threemove sequence: 25...♖d8 26.♘b3 ♕c8 27.♖xd8+ ♕xd8 28.♘xa5.’

25...♖d8 26.♘b3 ♕c8 27.♖xd8+ ♕xd8 28.♘xa5.’

This is a really powerful way of replicating the uncertainty and feelings of doubt that you have during a game where you’re always nervous you’ll miss something – both for yourself and against yourself!

I was very impressed by this book and I definitely think that working through these exercises will be of benefit to any player rated in the target audience of 1500-1800 and quite possibly somewhat higher too! Good stuff: four stars!

As the Candidates has ended and Gukesh has emerged as the next World Championship challenger, Ding Liren’s Best Games by Davorin Kuljasevic (New In Chess) is a welcome chance to reflect on the challenge Gukesh will face and to reacquaint ourselves with our current World Champion! This 326-page book presents 58 games/extracts played between 1996 and 2023 when Ding defeated Ian Nepomniachtchi to take the coveted crown.

As the Candidates has ended and Gukesh has emerged as the next World Championship challenger, Ding Liren’s Best Games by Davorin Kuljasevic (New In Chess) is a welcome chance to reflect on the challenge Gukesh will face and to reacquaint ourselves with our current World Champion! This 326-page book presents 58 games/extracts played between 1996 and 2023 when Ding defeated Ian Nepomniachtchi to take the coveted crown.

A couple of introductory chapters sketch Ding’s career and give an overview of his style, before the book moves chronologically through Ding’s games. Most are annotated by Kuljasevic but there are also eleven games annotated by Ding himself. A final chapter sets eighteen exercises from Ding’s games. Before reading the book, my feeling about Ding was composed of limited but conflicting impressions. There was the solid Ding I remembered from the 2018 Berlin Candidates who drew so many games (13 of the 14!) and then there was the rollercoaster blunder-filled ride of the 2023 World Championship match! There were also some truly magical tactical games – a critical penultimate round against Duda at the 2018 Batumi Olympiad, and an amazing victory against Bai Jinshi in the 2017 Chinese Team Championships – to throw into this confusing mix!

Before reading the book, my feeling about Ding was composed of limited but conflicting impressions. There was the solid Ding I remembered from the 2018 Berlin Candidates who drew so many games (13 of the 14!) and then there was the rollercoaster blunder-filled ride of the 2023 World Championship match! There were also some truly magical tactical games – a critical penultimate round against Duda at the 2018 Batumi Olympiad, and an amazing victory against Bai Jinshi in the 2017 Chinese Team Championships – to throw into this confusing mix!

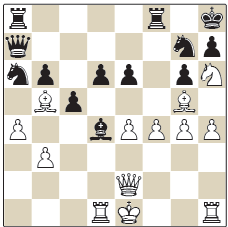

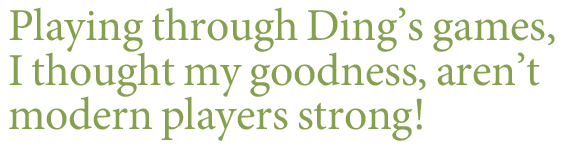

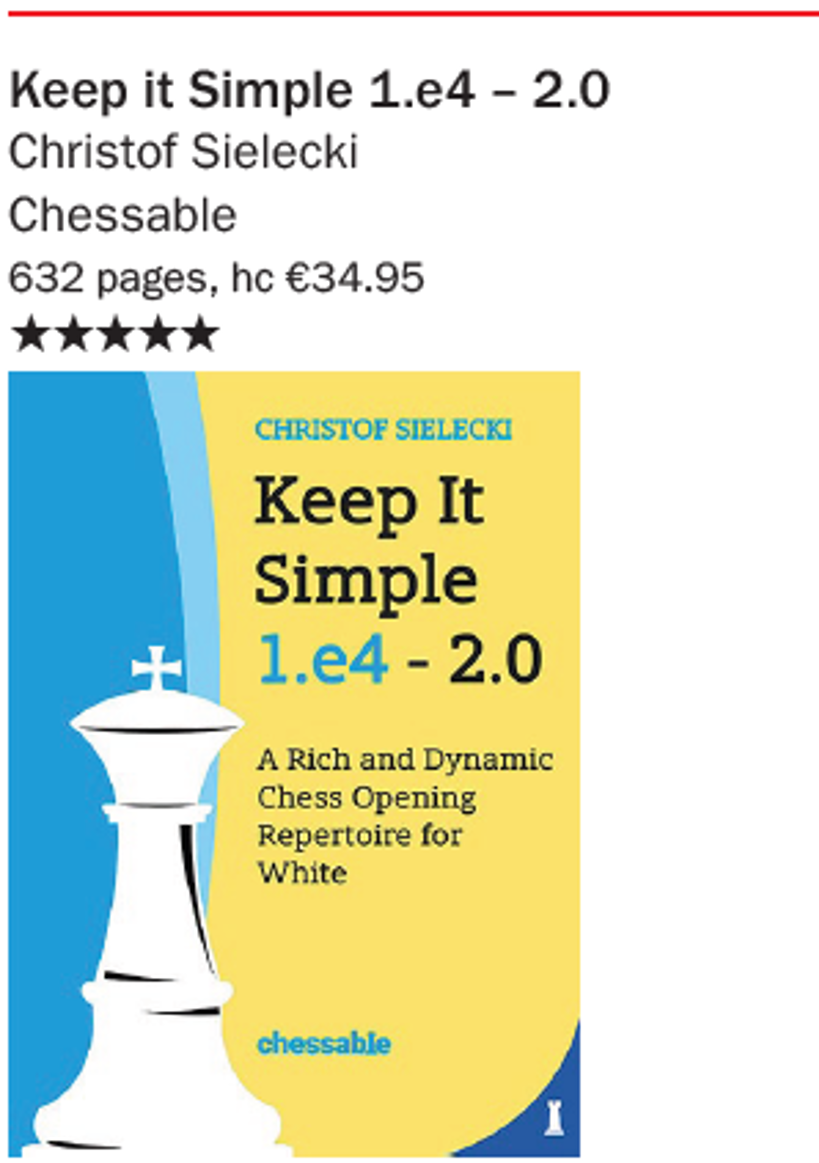

Bai Jinshi

Ding Liren

China 2017 21.h3 h5 22.♗h2 g4+ 23.♔g3 ♖d2 24.♕b3 ♘e4+ 25.♔h4 ♗e7+ 26.♔xh5 ♔g7 27.♗f4 ♗f5 28.♗h6+ ♔h7 29.♕xb7 ♖xf2 30.♗g5 ♖h8 31.♘xf7 ♗g6+ 32.♔xg4 ♘e5+ 0-1.

21.h3 h5 22.♗h2 g4+ 23.♔g3 ♖d2 24.♕b3 ♘e4+ 25.♔h4 ♗e7+ 26.♔xh5 ♔g7 27.♗f4 ♗f5 28.♗h6+ ♔h7 29.♕xb7 ♖xf2 30.♗g5 ♖h8 31.♘xf7 ♗g6+ 32.♔xg4 ♘e5+ 0-1.

Playing through the games, I guess I had similar feelings as when I read through a biography of Caruana – my goodness, aren’t modern players strong! There really is more or less everything in this game collection: fine endings, wonderful tactics, great preparation, lovely ideas. You really do hope that Ding can get his motivation and calm back to reach his top level again because his maximum level is deeply impressive! All-in-all, a welcome reminder of the strength of our current World Champion! Four stars!

Keep it Simple 1.e4 – 2.0 by Christof Sielecki is the latest in a steady stream of Chessable course crossovers into print publishing. I’ve mentioned before how beautifully-produced they are with a hardback cover, colour pages and a very pleasant letter-type to read.

Keep it Simple 1.e4 – 2.0 by Christof Sielecki is the latest in a steady stream of Chessable course crossovers into print publishing. I’ve mentioned before how beautifully-produced they are with a hardback cover, colour pages and a very pleasant letter-type to read.

I did a slight double-take though when I first spotted the book as it’s a pretty hefty volume: 632 pages! How simple is the content going to be when it takes so many pages to explain? Well, despite the size of the book, I thought Sielecki did a very good job!

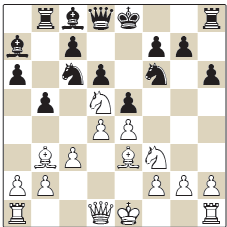

The book provides a complete opening repertoire for White based around 1.e4, focusing on solid, durable lines. For example, 1...e5 is met by the Ruy Lopez with 5.d3 (1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗b5 a6 4.♗a4 ♘f6 5.d3) and 1...c5 is met either by 3.♗b5 systems (1.e4 c5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗b5 and 1.e4 c5 2.♘f3 d6 3.♗b5+) or by a transposition back to the c3 Sicilian (1.e4 c5 2.♘f3 e6 3.c3). Reading this book during the Candidates with its proliferation of Exchange Frenches (also via the Petroff move order 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘f6 3.♘xe5 d6 4.♘f3 ♘xe4 5.d3 ♘f6 6.d4 d5) part of me did wonder whether Sielecki regretted switching to the Tarrasch (1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.♘d2) after recommending the Exchange French in the first edition of this course!

There are a few different approaches to drawing up a complete opening course for White like this. At the extremes, you can pick a single setup or pawn structure (something like the King’s Indian Attack for example) and use it against as many Black systems as you can manage, or you take the grandmaster repertoire approach where you pick the best concrete line for each situation. Both have drawbacks of course.

The single setup approach gets you up and running quickly but it flattens the skills you need to play openings well: an appreciation of move orders, and the alertness of mind to adjust to the subtleties of different opening setups. The grandmaster repertoire approach is extremely memory-intensive and the risk is that rote-learning replaces understanding of why moves are chosen in each specific situation.

Sielecki manages a good blend of both approaches. For example, in both the Lopez and Sicilian recommendations, White often aims for a double pawn centre with c3 and d4 which gives a feeling of continuity across different systems.

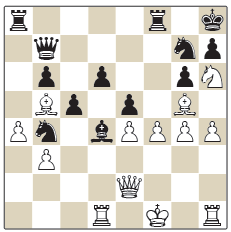

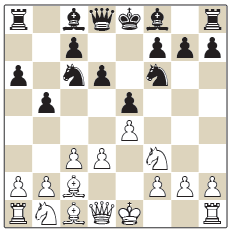

Move-order subtlety with ♘c3:

1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗b5 a6 4.♗a4 ♘f6 5.d3 b5 6.♗b3 ♗c5 7.♘c3 h6 8.♘d5 d6 9.c3 ♖b8 10.d4 ♗a7 11.♗e3

The classic set-up:

1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗b5 a6 4.♗a4 ♘f6 5.d3 d6 6.c3 b5 7.♗c2

A c3 and d4 centre against the Sicilian:

1.e4 c5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗b5 e6 4.0-0 ♘ge7 5.♖e1 a6 6.♗f1 ♘g6 7.c3

Then Sielecki’s choice of systems tend to contain a little move-order subtlety but not too much to become confusing to learn. For example, against 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗b5 a6 4.♗a4 ♘f6 5.d3 b5 6.♗b3 ♗c5 or 6...♗e7, Sielecki advocates a general approach with ♘c3; in quieter lines with an early d6, Sielecki wants the typical Ruy Lopez knight transfer ♘b1-d2-f1-g3 combined with c3, 0-0 and ♖e1. This introduces the student to a range of ideas without becoming overwhelming while many of the lines could be played reasonably along these general lines without needing to remember exact variations.

Perhaps the only opening that made me frown a little was the Tarrasch against the French. Certainly after 3...♘f6 lines, lines such as 4.e5 ♘fd7 5.c3 c5 6.f4 ♘c6 7.♘df3 cxd4 8.cxd4 ♗b4+ 9.♔f2 ♕b6 10.♗e3 f6 11.h4 are not very intuitive to learn. However, this line was chosen partly from reflection on student feedback complaining about the sterility of the Exchange French positions recommended in the first edition... It’s hard to please everyone!

are not very intuitive to learn. However, this line was chosen partly from reflection on student feedback complaining about the sterility of the Exchange French positions recommended in the first edition... It’s hard to please everyone!

In summary, a very good opening repertoire full of sensible lines and good suggestions. It’s somewhere between four and five stars for me but happy to bump that up to a five! ■