These book reviews by Matthew Sadler were published in New In Chess magazine 2024#5

Milos Pavlovic has managed to write an interesting book full of boring openings. But luckily a massive endgame manual by Jacob Aagaard works pretty well as entertainment rather than just as instruction.

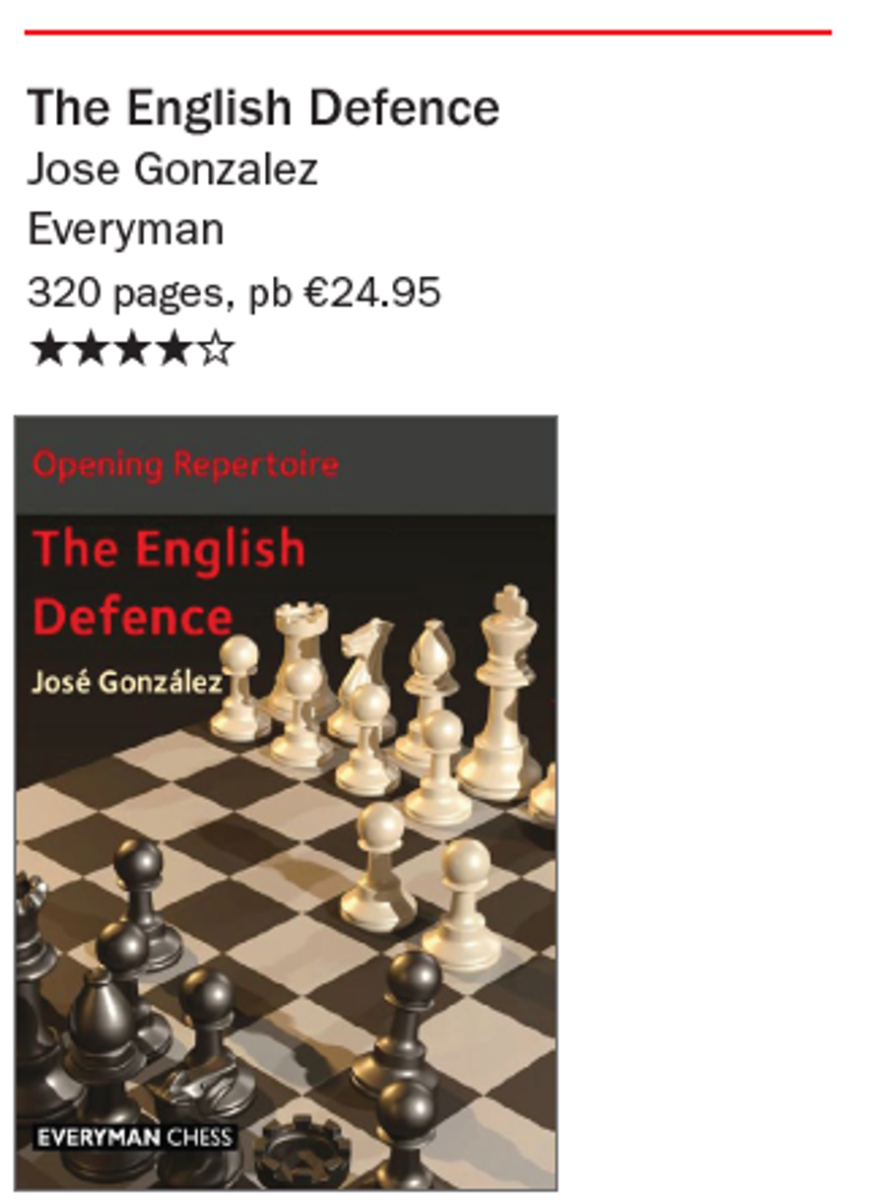

After the recent European Championship football final, The English Defence (Everyman) feels like a risky topic for Spanish Grandmaster Jose Gonzalez to put in front of an English reviewer!

After the recent European Championship football final, The English Defence (Everyman) feels like a risky topic for Spanish Grandmaster Jose Gonzalez to put in front of an English reviewer!

In 316 pages, Gonzalez presents a complete repertoire for Black based around 1.d4 e6, which has been the perennial favourite of English free spirits such as Plaskett, Keene, Miles and Speelman (even Sadler sometimes ☺). Gonzalez also takes care to deal with all the annoying ways that White can avoid this line, most notably 2.♘f3 (recommending a lovely Rapport Stonewall Dutch line also analysed by Sedlak for Quality Chess) and 2.e4 (with a transposition back to the French).

Reading the book made me somewhat nostalgic. In my professional days, the English Defence (1.d4 e6 2.c4 b6) was a perennial risk when facing Tony Miles and Jon Speelman and I spent a vast amount of time preparing a very sharp line against it. I got my chance at the super-strong Koge Open of 1997 against the strong Latvian grandmaster Edvins Kengis,also a well-known 1...b6 addict.

I still remember playing through my lines before the game and suddenly noticing something...

Matthew Sadler

Edvins Kengis

Koge 1997

English Defence

1.d4 e6 2.c4 b6 3.e4 ♗b7 4.♘c3 ♗b4 5.f3 f5 6.exf5 ♘h6 7.fxe6 ♘f5 8.♗f4 dxe6

Against Thomas Luther at Hastings 1995/96, I scored a rapid victory after the misstep 8...0-0, which allows White to develop without difficulties: 9.♕d2 dxe6 10.0-0-0 (lovely harmonious development and a sensitive weakness on e6 to target) 10...♘c6 11.d5 ♘a5 12.♘h3 ♕e8 13.♖e1 ♗xc3 14.♕xc3 ♕a4 15.b4 ♕xa2 16.bxa5 exd5 17.♗d3 d4 18.♕b2 ♕a4 19.♘g5 bxa5 20.♘e6 ♖fb8 21.♘c5 ♕c6 22.♕b5 ♕xb5 1-0.

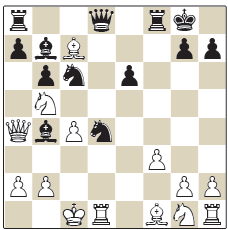

9.♕a4+ ♘c6

This position was known to me from the crazy game Lev-Kengis, London 1991, which I’d witnessed in person! Black was fine in that game after Lev’s 10.d5 although he lost in the end. But I’d prepared something better!

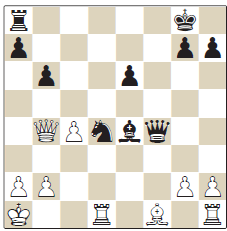

10.0-0-0 ♘xd4 11.♘b5

This was my big idea. It certainly came as a big surprise to Kengis, who went into one of his customary long thinks.

11...0-0 12.♗xc7 This looks quite engine-like, although since it was conceived in 1996, I’m pretty certain it was all my genius ☺.

This looks quite engine-like, although since it was conceived in 1996, I’m pretty certain it was all my genius ☺.

The bishop on f4 was attacked after 11...0-0 so the bishop moves away with tempo and leaves Black with the problem of dealing with the loose knight on d4 and the bishop on b4.

Kengis played the inferior 12...♕e7 and I ended up messing up a great chance to move to the top of the tournament... but that’s another story, and another trauma!

12...♕g5+ was my main line.

13.f4 ♕h6

13...♖xf4 14.♘h3 was the first point, which is pretty sweet, you have to admit!

14.♘xd4 ♖xf4 15.♗xf4 ♕xf4+ 16.♔b1 ♘xd4

And now my idea was the brilliant 17.♗d3 ♗xg2 18.♘h3, which is also quite attractive! The knight’s potential for jumping into g5 seemed very useful and after 18...♕e3 19.♖hg1, I was planning to meet 19...♗e4 with 20.♘f2.

Unfortunately I realised a couple of hours before the game with a sinking feeling that after 19.♖hg1, Black had 19...♗d2 and I couldn’t even find equality! Some frantic analysis, punctuated by peaks of elation and troughs of despairs led me to:

Some frantic analysis, punctuated by peaks of elation and troughs of despairs led me to:

17.♘f3 ♘xf3 18.♕xb4 ♗e4+ 19.♔a1

19.♗d3 ♗xd3+ 20.♖xd3 ♕f5 followed by ...♘e5 regains the exchange, with a comfortable position for Black.

19...♘d4 20.♕d2 ♘c2+ 21.♔b1 ♘b4+ 22.♔a1

20.♕d2 ♘c2+ 21.♔b1 ♘b4+ 22.♔a1

22.♔c1 ♘xa2 mate.

22...♘c2+

And a draw by repetition.

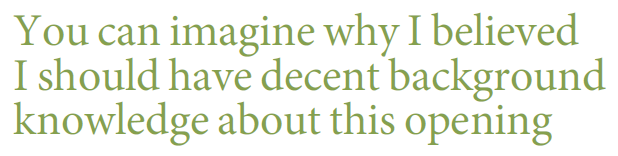

After the tournament, I must have spent another couple of days trying to find the elusive ‘win’ for White but failed... and of course nowadays the engine just shows you this whole drawn line after a couple of milliseconds after 11.♘b5! My apologies for this extended digression – an old theoretician will insist on recounting his war stories ☺. You can imagine though, why I believed I should have a decent level of background knowledge about this opening, even after all these years. So it was a bit shocking to notice Gonzalez’ recommendation of the important move order 1.d4 e6 2.c4 b6 3.♘c3 ♗b4+ (instead of 3...♗b7) as the key to making this line playable for Black.

My apologies for this extended digression – an old theoretician will insist on recounting his war stories ☺. You can imagine though, why I believed I should have a decent level of background knowledge about this opening, even after all these years. So it was a bit shocking to notice Gonzalez’ recommendation of the important move order 1.d4 e6 2.c4 b6 3.♘c3 ♗b4+ (instead of 3...♗b7) as the key to making this line playable for Black. I won’t detail the exact reasons here (you’ll need the book for that!) but I confess to a feeling of complete inadequacy when thinking of all the time I’d spent on this line (with both colours) while remaining unaware of a crucial moment as early as the third move!

I won’t detail the exact reasons here (you’ll need the book for that!) but I confess to a feeling of complete inadequacy when thinking of all the time I’d spent on this line (with both colours) while remaining unaware of a crucial moment as early as the third move!

The book’s pretty good though!

The only thing I wasn’t particularly impressed with was the recommendation of the Fort Knox (1.d4 e6 2.e4 d5 3.♘c3 dxe4 4.♘xe4 ♗d7) if White were to switch back to a 1.e4 opening. I would really recommend spending some proper time on a good French repertoire if you want to play 1.d4 e6 with Black.

This goes back to my experiences with preparing for White games against Tony Miles. At some stage I noticed that despite playing 1.d4 e6 very frequently, he had virtually no French games. I realised then that he only ventured it when he was confident the opponent wouldn’t play 2.e4! His French repertoire turned out to be a big weakness...

Matthew Sadler

Tony Miles

Hove 1997

French Defence

1.d4 e6 2.e4 d5 3.♘d2 dxe4 4.♘xe4 ♘d7 5.♗d3 ♘gf6 6.♕e2 c5 7.♘xf6+ ♘xf6 8.dxc5 ♗xc5 9.♗d2 0-0 10.0-0-0 ♕d5 11.♗c3 ♕g5+ 12.♔b1 ♘d5 13.♗e5 ♕xg2 14.♕h5 f5 15.♘f3 ♕g4 16.♖hg1 ...and you can guess the rest! After that, Tony didn’t play 1.d4 e6 against me again. So spend some time getting the French right!

...and you can guess the rest! After that, Tony didn’t play 1.d4 e6 against me again. So spend some time getting the French right!

The book’s somewhere between 3 and 4 stars for me, but let me show true English gentlemanly spirit and award it 4 stars!

I’ve had Milos Pavlovic’s Strategic Play with 1.d4 (Everyman) on my ‘to review’ pile for a little while now. I’m not quite sure why it stayed there that long – possibly the rather sober title didn’t get my reviewer’s juices flowing! I guess I’d describe it as an interesting book full of boring openings ☺.

I’ve had Milos Pavlovic’s Strategic Play with 1.d4 (Everyman) on my ‘to review’ pile for a little while now. I’m not quite sure why it stayed there that long – possibly the rather sober title didn’t get my reviewer’s juices flowing! I guess I’d describe it as an interesting book full of boring openings ☺.

In 279 pages, Pavlovic builds a complete repertoire around the first three moves 1.d4, 2.♘f3 and 3.g3, looking to achieve minimal advantages in completely safe positions that are totally uninspiring for the opponent. Older readers may be triggered to recall Edmar Mednis’s From the Opening into the Endgame, which is similar in spirit and identical in some recommendations.

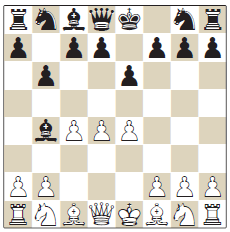

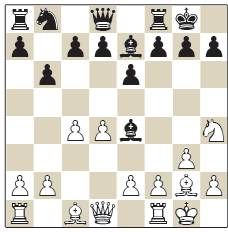

For example, this Queen’s Indian:

1.d4 ♘f6 2.♘f3 e6 3.g3 b6 4.♗g2 ♗b7 5.0-0 ♗e7 6.c4

Note the move-order with a delayed c4 which avoids all manner of additional Black setups (such as 4.c4 ♗a6)

6...0-0 7.♘c3 ♘e4 8.♘xe4 ♗xe4 9.♘h4 Yep, White is draining all the life out of Black’s Queen’s Indian with these exchanges!

Yep, White is draining all the life out of Black’s Queen’s Indian with these exchanges!

9...♗xg2 10.♘xg2 d5 11.♕a4

It’s no surprise that this – and other systems in the book – are favourites of Ulf Andersson! The first game in the book features a smooth and easy win by Ulf against Simen Agdestein.

I was slightly equivocal about the book’s qualities. I definitely think that this book is a good way to pick up some irritating lines to frustrate your opponents, and the openings are well-chosen for this purpose. I guess there were just a couple of things missing to make this a really topnotch book. Firstly, it would have been interesting to know and discuss what the proposed engine response is to each of the recommendations. After all, once your games get into the databases, then that’s what you’ll be facing!

Firstly, it would have been interesting to know and discuss what the proposed engine response is to each of the recommendations. After all, once your games get into the databases, then that’s what you’ll be facing!

Secondly, I felt that some discussion of the games of the players like Ulf Andersson, Oleg Romanishin and Vasily Smyslov (who have played a lot of the system in the book) might give the reader some insight into the right mindset and approach for playing their openings.

All in all however, worth a read for an initiation into the dark arts of tailoring your openings to limit rather than destroy! 3 stars!

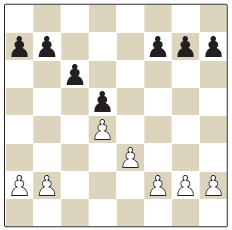

Typical Queen’s Gambit Exchange Variation by Karsten Müller is the latest in an ongoing series based around a really nice idea. Müller gathers together roughly 100 puzzles demonstrating typical themes (tactical and positional) from a specific opening. This particular book basically takes the Carlsbad structure of the Queen’s Gambit Declined as the starting point...

Typical Queen’s Gambit Exchange Variation by Karsten Müller is the latest in an ongoing series based around a really nice idea. Müller gathers together roughly 100 puzzles demonstrating typical themes (tactical and positional) from a specific opening. This particular book basically takes the Carlsbad structure of the Queen’s Gambit Declined as the starting point... ...and tweaks the pawn structure slightly throughout the examples. It’s a truly super idea to build up experience in a particular pawn structure or opening and I definitely think that any player will benefit from working through these examples.

...and tweaks the pawn structure slightly throughout the examples. It’s a truly super idea to build up experience in a particular pawn structure or opening and I definitely think that any player will benefit from working through these examples.

However, there are a couple of things missing that make the experience of solving these puzzles less comfortable than I would like. (By the way, this complaint may be partly a result of my feeling somewhat mentally drained after an exhausting – ongoing – period at work which means I need all the help I can get to accomplish anything mentally challenging!)

What I find quite difficult about Müller’s puzzles is that I’m never sure how much time I should spend on them and whether I should find them easy or difficult. Some solutions seem to jump out at me immediately whereas others make my brain hurt as they appear to require precise calculation. Moreover, Müller doesn’t really give guidance as to the expected evaluation of the solution: am I looking for a slight advantage or a clear advantage? Obviously, knowing this helps you to gauge how much effort you should put into a puzzle.

You can argue that giving minimal instructions helps to replicate the conditions during a game. However, I’m getting to the stage in my chess career where I’m happy to be spending any time at all on chess and looking more for a positive sense of achievement rather than a hard slog! All in all I really like the concept (including the Müller-patented novelty of a QR code above each puzzle so you can look up the solution online!) but would really appreciate a bit of extra help to make life a little easier! Somewhere between 3 and 4 stars for me – I’ll give 3 this time!

All in all I really like the concept (including the Müller-patented novelty of a QR code above each puzzle so you can look up the solution online!) but would really appreciate a bit of extra help to make life a little easier! Somewhere between 3 and 4 stars for me – I’ll give 3 this time!

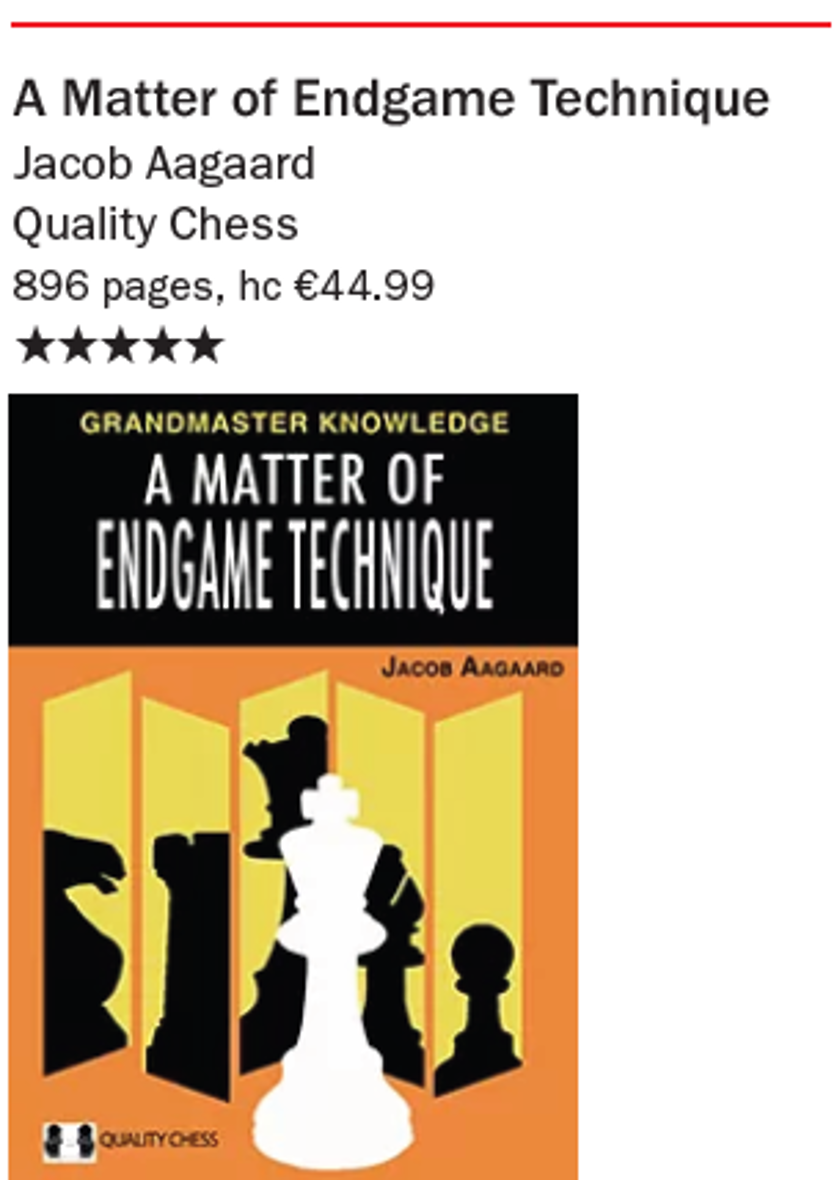

Fans of English radio comedy (I may be losing a few of you here, I know!) will be familiar with the panel quiz I’m Sorry I Haven’t a Clue, where contestants play a series of silly games such as ‘One song to the tune of another’ and the immortal ‘Mornington Crescent’. Another favourite is ‘Good News, Bad News’, in which contestants have to alternate pieces of good and bad news. As you’d expect, by the end the good and bad news is pretty hard to tell apart (Good news: they are raising the motorway speed limit. Bad news: you can reach 10 miles an hour on the M25. Good news: the M25 is the only motorway where you can have your car windscreen washed in the fast lane. Bad news: You can also get your tyres pinched) I got echoes of this when reading the introduction to Jacob Aagaard’s monster 900-page A Matter of Endgame Technique (Quality Chess) As Jacob put it: ‘On the one hand, it is a lot of information, but on the other, it is a big challenge as well’. I was expecting something a little more consoling after that ‘but’!

Fans of English radio comedy (I may be losing a few of you here, I know!) will be familiar with the panel quiz I’m Sorry I Haven’t a Clue, where contestants play a series of silly games such as ‘One song to the tune of another’ and the immortal ‘Mornington Crescent’. Another favourite is ‘Good News, Bad News’, in which contestants have to alternate pieces of good and bad news. As you’d expect, by the end the good and bad news is pretty hard to tell apart (Good news: they are raising the motorway speed limit. Bad news: you can reach 10 miles an hour on the M25. Good news: the M25 is the only motorway where you can have your car windscreen washed in the fast lane. Bad news: You can also get your tyres pinched) I got echoes of this when reading the introduction to Jacob Aagaard’s monster 900-page A Matter of Endgame Technique (Quality Chess) As Jacob put it: ‘On the one hand, it is a lot of information, but on the other, it is a big challenge as well’. I was expecting something a little more consoling after that ‘but’!

I will confess that the size of the book did cause me a considerable mental challenge. I kept on walking past it, lifting the cover up, peeking inside and then quickly running away ☺. However, eventually I manned up and sat down to read it seriously and I was very happy I did!

The books is divided into six chapters. Chapter 1 deals with ‘Endgame Elements’ which covers all the ‘simple’ building blocks of endgame play such as distant passed pawns, zugzwang, triangulation, king activity... 73 elements in total! Chapter 2 is called ‘Lack of technique’, which causes any reader to skip quickly to the index to check none of his games are included!

It’s full of interesting examples of how strong players failed to convert their advantages cleanly (though often still winning when their opponents lost faith or concentration). Chapter 3 is a really interesting examination of fortresses and that leads us (on page 545!) to Chapter 4, which examines rook against bishop endgames. Chapter 5 looks in depth at the problem of exchanges and finally (on page 739!) we start Chapter 6, which analyses fourteen illustrative games with an endgame theme (plus another one without an endgame!). There is a generous selection of puzzles before each chapter, each clearly organised by level of difficulty. Without a doubt I can think back to various stages in my career when I would have absolutely devoured a book like this. Part of my daily training when I started as a professional (aged sixteen) was to play through (and repeat perfectly) a series of endgames I considered typical and useful, culled from Averbakh’s Pergammon endgame series and Lajos Portisch’s Six Hundred Endings. It normally took me a couple of hours and while I was doing so, I had the uneasy feeling that despite this marvellous discipline, I wasn’t learning very much about how to approach or understand the endgame (which was undoubtedly true). Unfortunately, I didn’t have the intelligence to run with that vague unease and make something better for myself, but if I had, I’m pretty sure I would have wanted it to look like Aagaard’s first chapter!

Without a doubt I can think back to various stages in my career when I would have absolutely devoured a book like this. Part of my daily training when I started as a professional (aged sixteen) was to play through (and repeat perfectly) a series of endgames I considered typical and useful, culled from Averbakh’s Pergammon endgame series and Lajos Portisch’s Six Hundred Endings. It normally took me a couple of hours and while I was doing so, I had the uneasy feeling that despite this marvellous discipline, I wasn’t learning very much about how to approach or understand the endgame (which was undoubtedly true). Unfortunately, I didn’t have the intelligence to run with that vague unease and make something better for myself, but if I had, I’m pretty sure I would have wanted it to look like Aagaard’s first chapter!

Looking at the book now with a chess career much more behind me than in front of me, it’s hard not to suppress a feeling of despair at what I must have missed in the endgames I played despite being a reasonably strong player. So many tactics, so many subtle points that I must have blundered through without noticing!

Luckily A Matter of Endgame Technique also works pretty well as entertainment rather than just as instruction. That’s due mainly to Aagaard’s scrupulous avoidance of any of the hackneyed classic material you invariably come across in most endgame books. That makes the book equally a journey of discovery, that you can enjoy without worrying about needing to learn a lesson at every turn of the page! Ironically, my favourite example (quite near the front of the book) features a game from 1967... of which I was completely unaware! It’s in the section called ‘Unstoppable Promotion’ and was played between Duncan Suttles and Lubomir Kavalek at the Sousse Interzonal.

Duncan Suttles

Lubomir Kavalek

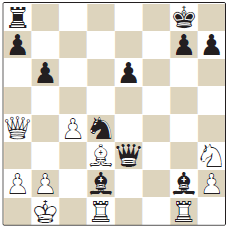

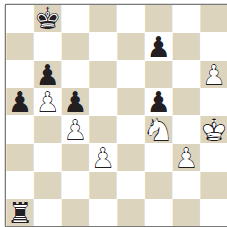

Sousse Interzonal 1967 position after 41.♔h4

position after 41.♔h4

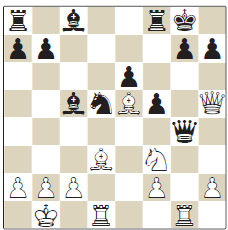

The game was agreed drawn in this position, presumably after White’s sealed move. Aagaard does some fantastic analysis to show that Black is winning. The key feature is Black’s ability to stop the pawn by bringing the rook back to his first rank with ...♖e1-e8 while the white knight struggles to stop Black’s distant a-pawn.

However, as you’d expect with Aagaard’s examples, there are many beautiful and unexpected tactics along the way!

41...♖h1+

41...♖e1 would lead to a far-from obvious draw but let’s focus on the beautiful main line!

42.♔g5

42.♘h3 ♖e1 would obviously be a big improvement for Black: that white knight will never reach the a-pawn now! 42...♔b7

42...♔b7

An amazing move!

42...a4 43.♘h5 ♖e1 and now the lovely 44.♘g7 stops ...♖e8! and would lead to a draw by repetition after 44...♖h1 45.♘h5. But what’s so different about 42...♔b7 ?

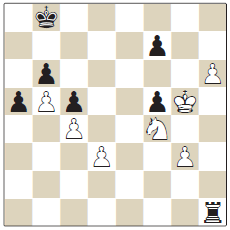

43.♘h5 f4

That’s it! It’s rather more important for Black’s counterplay that White’s h-pawn should not queen with check!

44.h7

44.gxf4 ♖g1+ 45.♔f5 ♖g6 46.h7 ♖h6 stops the h-pawn and then Black’s a-pawn runs!

44...fxg3 45.h8♕ g2 The g-pawn is unstoppable! Note that the black king couldn’t go to c7 on move 42, else ♕e5+ would pick up the g-pawn in a few moves.

The g-pawn is unstoppable! Note that the black king couldn’t go to c7 on move 42, else ♕e5+ would pick up the g-pawn in a few moves.

46.♕e5 g1♕+ 47.♘g3 It still looks tricky for Black to finish off as his king is exposed to checks.

It still looks tricky for Black to finish off as his king is exposed to checks.

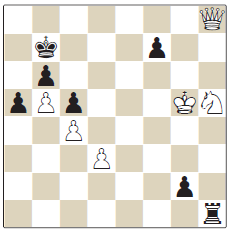

However, give yourself a puzzle: Black to play and win (two-move solution!)

47...f6+ 48.♔xf6 ♕a1

Exquisite!

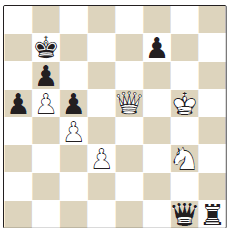

49.♘xh1 ♕xe5+ 50.♔xe5 a4

And now the a-pawn cannot be stopped!

Pretty cool, and typical of the surprises in store for the reader throughout the book’s many pages!

It’s a really great book, and essential reading for anyone wanting to improve their endgame play, or simply to gaze in wonder at the amazing ability of chess to become ever more complicated and subtle as the number of pieces on the board decreases! 5 stars! ■