These book reviews by Matthew Sadler were published in New In Chess magazine 2024#6-7

The modern world is a confusing place. Aren’t chess players lucky to live in this rational parallel world, where an engine can provide clarity in any position? Or should we ignore the objective truth, take risks, embrace chaos and strive to use our intuition creatively?

The modern world is a confusing place. And it’s not just what happens that’s baffling. The biggest confusion lies ahead when you try to form a view! You wade through myriad explanations of what has happened and why, amid a deluge of fake news and bots. All the while, you’re aware that your own prejudices (some conscious, some inferred by algorithms) limit the breadth of opinions you are exposed to. It makes you long for the rational world of chess, where an engine can show you the guaranteed best move in any position...

So why is my confusion in chess just as great as in life? After all, in chess, engines aren’t trying to trick me and I don’t need to be wary of malicious bots recommending blunders! (what a great hack that would be!)

In life you doubt what you know because you are overwhelmed by too many sources shouting out different things. In chess you doubt often because the engine appears unimpressed with standard wisdom – especially that wisdom you accumulated at such great effort during the precomputer age! It shows itself in even the most trivial ways.

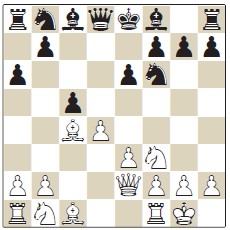

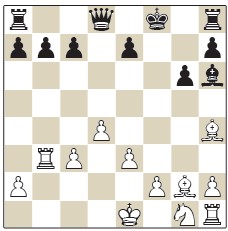

For example, I was playing through the game Stahlberg-Book, Kemeri 1937, from Peter Holmgren’s gorgeous Gideon Stahlberg – An Epoch in Swedish Chess – Volume 1 (Verendel Publishing) which featured a typical Queen’s Gambit Accepted:

Gideon Stahlberg

Eero Book

Kemeri 1937

1.d4 d5 2.c4 dxc4 3.♘f3 ♘f6 4.e3 e6 5.♗xc4 c5 6.0-0 a6 7.♕e2 Here Book played

Here Book played

7...♘c6

Hah, typical 1930s opening play, I thought to myself. Everyone knows now that the queen’s knight should go to d7 after ...b5 and ...♗b7. Keep the a8-h1 diagonal free for the light-squared bishop and let the knight cover the c5-square. I’ve shared this insight many times during commentary! However, let an engine like Torch analyse for some time and 7...b5 is evaluated at 0.19 and 7...♘c6 at 0.20. And then it dawns on you: what do I really know? If I were teaching a young talent, should I be repeating this age-old wisdom or do I need to change my ideas completely? Accept that what I used to see as objective truth was never more than a personal preference?

You can see why creating a chess engine that could explain its own moves would be an amazing breakthrough, and I was recently pointed to a scientific study that tried to do just this. Essentially the scientists were trying to visualise the squares and pieces that an engine predicted would be important in a given position. They did so with colour heatmaps. A piece or square predicted as important would colour towards blue while a piece or square predicted less important would colour towards red. Inevitably however, the explanations raised even more questions than the selected move! Why on earth was this square important to the engine in this position?

Perhaps it’s simply unrealistic to expect engines to explain their decisions in our terms (e.g., better pawn structure, weak king) because our terms simply aren’t rich enough to capture what the engines are seeing. I’ve discussed this many times with TCEC chatter mrbdzz and he suggested that chess demonstrates that everything has a limit of simplification (he gives it the lovely term ‘computational irreducibility’). You can’t go past that point without losing important details (which is what always happens with these automated explainers). Perhaps we ourselves somehow still need to evolve (our terminology) a bit to get closer to what the engines could share with us.

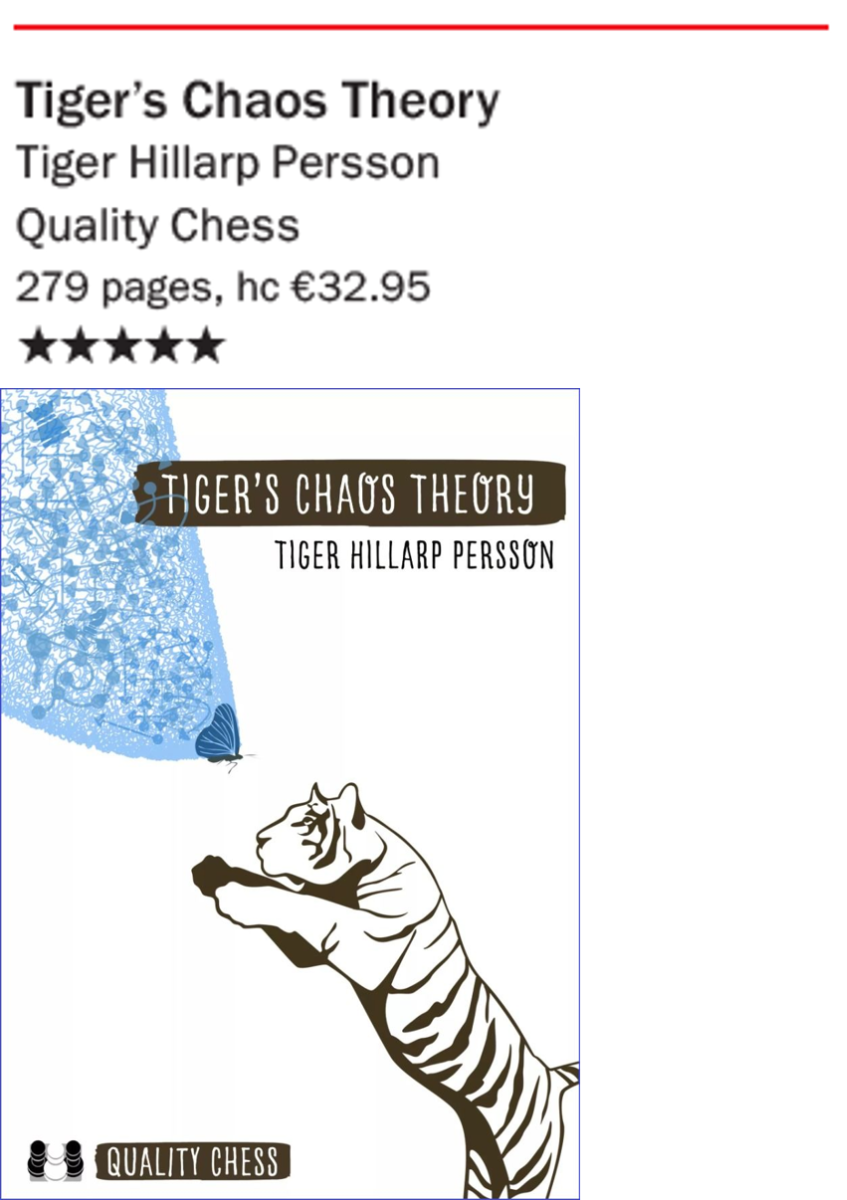

Why did I get on to this subject? Well it was all the fault of the books I’ve been reading this month starting with Tiger’s Chaos Theory by Swedish grandmaster Tiger Hillarp Persson (Quality Chess). The title is intriguing so what is this 278-book of 12 chapters – with such titles as ‘Hecatomb’ and ‘When 5+5 > 10’ – all about? Well even that took me a little while to grasp! I’d say that the Preface and Introduction is mostly Tiger figuring out exactly what he is going to write about!

Why did I get on to this subject? Well it was all the fault of the books I’ve been reading this month starting with Tiger’s Chaos Theory by Swedish grandmaster Tiger Hillarp Persson (Quality Chess). The title is intriguing so what is this 278-book of 12 chapters – with such titles as ‘Hecatomb’ and ‘When 5+5 > 10’ – all about? Well even that took me a little while to grasp! I’d say that the Preface and Introduction is mostly Tiger figuring out exactly what he is going to write about! I was fearing this might turn out to be a slightly wearying read but I needn’t have worried: the rest is wonderfully entertaining. I’d describe this book as a first map of waters that we’ve always assumed are unchartable. I thought that Tiger summed the book up well in a section on Intuition and Calculation:

I was fearing this might turn out to be a slightly wearying read but I needn’t have worried: the rest is wonderfully entertaining. I’d describe this book as a first map of waters that we’ve always assumed are unchartable. I thought that Tiger summed the book up well in a section on Intuition and Calculation:

‘If I am too optimistic, I tend to skip through the calculation part so as not to ruin my good mood. If my game goes badly, I blame my intuition for “being out of tune”. My relationship with calculation is, at the best of times, dysfunctional. My relationship with intuition is slightly less so. I have continued to fine-tune my ability to pick up patterns and improve my intuition over almost three decades.

This book is my best effort to teach what I learnt from deconstructing my strengths. This book is not so much ‘about creativity’ as it is a map towards improving the reader’s intuition in some rather extreme areas. At first I thought I was writing a book about creativity, but it turned out to be a book about intuition; or perhaps on how to use intuition creatively.’

What are those ‘rather extreme areas’? Well, I don’t want to ruin the book for you by quoting too extensively from it, and I also think that a short quote wouldn’t really get across how amazing some of the analysis and the insights are. Let me instead just share two positions from his games that Tiger delves into and you’ll understand what you can expect from the whole book. Firstly, from the chapter ‘Hecatomb’ (which addresses large sacrifices of material):

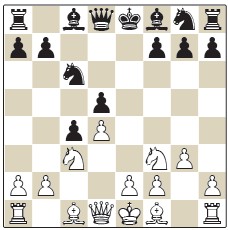

Tiger Hillarp Persson

Victor Mikhalevski

Reykjavik Open 2008

Grünfeld Defence, Stockholm Variation

1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 g6 3.♘c3 d5 4.♗g5 ♘e4 5.♗h4 ♘xc3 6.bxc3 dxc4 7.e3 ♗e6 8.♖b1 ♘d7 9.♕a4 ♗d5 10.♗xc4 ♗xg2 11.♕b3 ♗h6 12.♗xf7+ ♔f8 13.♗d5 ♘c5 14.♗xg2 ♘xb3 15.♖xb3 And secondly, from the chapter Where Pieces Cannot Go (self-explanatory!):

And secondly, from the chapter Where Pieces Cannot Go (self-explanatory!):

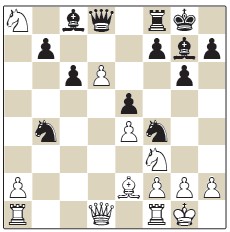

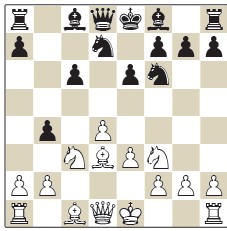

Peter Heine Nielsen

Tiger Hillarp Persson

Copenhagen Politiken Cup 1998

King’s Indian Defence, Bayonet Attack

1.c4 g6 2.d4 ♗g7 3.e4 d6 4.♘c3 ♘f6 5.♗e2 0-0 6.♘f3 e5 7.0-0 ♘c6 8.d5 ♘e7 9.b4 a5 10.♗a3 ♘h5 11.c5 axb4 12.♗xb4 ♘f4 13.♘b5 c6 14.♘c7 ♘exd5 15.♘xa8 ♘xb4 16.cxd6 Part of me wonders how an engine would explain these types of positions to us! Well, Tiger gives us the human view of how the brilliant ideas in these games came about and the feelings (rational and irrational) he experienced while playing these positions, and that’s pretty good already. From a didactic point of view, the power of this book is that you look at all manner of positions about which you might have said ‘Nah, not for me’ while being accompanied by a guide who has actually taken the risks and played them in real games (not just analysed them). A really cool book! 5 stars!

Part of me wonders how an engine would explain these types of positions to us! Well, Tiger gives us the human view of how the brilliant ideas in these games came about and the feelings (rational and irrational) he experienced while playing these positions, and that’s pretty good already. From a didactic point of view, the power of this book is that you look at all manner of positions about which you might have said ‘Nah, not for me’ while being accompanied by a guide who has actually taken the risks and played them in real games (not just analysed them). A really cool book! 5 stars!

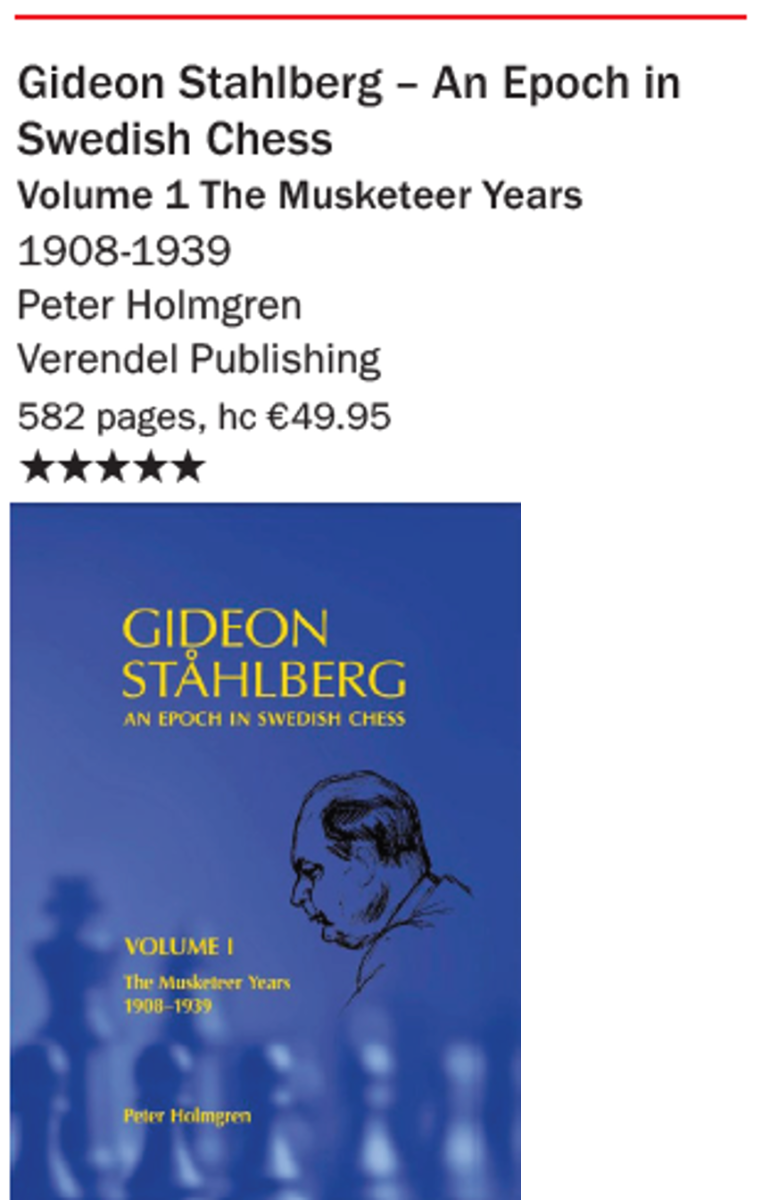

Next up is Gideon Stahlberg – An Epoch in Swedish Chess – Volume 1 The Musketeer Years 1908-1939 by Peter Holmgren (Verendel Publishing) and it’s so good! The great Swedish player Gideon Stahlberg is one of those players who – until now – had only managed to secure a bit part in my view of chess history. I first saw his name as a participant in the Zurich 1953 Candidates tournament, where he finished last, 3½ points behind 14th placed Max Euwe and 10 points behind the winner. And that more or less sealed my opinion of him until now: strong enough to qualify for the Candidates but not a patch on the top players. Well, you often come to realise that an opinion formed when you were just ten years old was rather lacking in nuance so I’m delighted to have the opportunity to update my opinion with this beautifully-produced hardback of 582 pages. The book covers the first period of Stahlberg’s career, from his birth in 1908 to the outbreak of World War II in 1939. The subtitle ‘The Musketeer Years’ refers to the group name given to the three top Swedish players of that era: Stahlberg, Stoltz and Lundin.

Next up is Gideon Stahlberg – An Epoch in Swedish Chess – Volume 1 The Musketeer Years 1908-1939 by Peter Holmgren (Verendel Publishing) and it’s so good! The great Swedish player Gideon Stahlberg is one of those players who – until now – had only managed to secure a bit part in my view of chess history. I first saw his name as a participant in the Zurich 1953 Candidates tournament, where he finished last, 3½ points behind 14th placed Max Euwe and 10 points behind the winner. And that more or less sealed my opinion of him until now: strong enough to qualify for the Candidates but not a patch on the top players. Well, you often come to realise that an opinion formed when you were just ten years old was rather lacking in nuance so I’m delighted to have the opportunity to update my opinion with this beautifully-produced hardback of 582 pages. The book covers the first period of Stahlberg’s career, from his birth in 1908 to the outbreak of World War II in 1939. The subtitle ‘The Musketeer Years’ refers to the group name given to the three top Swedish players of that era: Stahlberg, Stoltz and Lundin.

The book is a true biography, replete with tournament tables, photos and sketches. The descriptions of many of the lesser-known players against whom Stahlberg played (for example Swedish and German masters) is a particularly nice feature. The author says that the inclusion of these minibiographies delayed the publication of the book by more than a year(!) so let me say that they were definitely worth it in my view! The value of such a well researched biography is the insight that you also gain into the chess life of Sweden during that period. In all fairness, it had never ranked high on my list of things I wanted to know more about, but – with Holmgren as a guide – it turns out to be extremely interesting. Again, I only knew Stoltz and Lundin from the occasional games I had analysed or annotated (Stoltz’s glorious victory against Spielmann in the fifth game of their 1930 match and Lundin’s near-miss queen sacrifice against Bogolyubov in Stockholm 1930 are definitely worth a look) but those players also come to life for you in their interactions with Stahlberg. Holmgren has also done a fantastic job of tracing so many of Stahlberg’s games (including games played in local competitions or simultaneous displays) as well as many contemporary annotations, many by Stahlberg himself. It is worth noting that with the exception of a small number of games annotated by modern players, most of the games have not been computer-checked. I think that this is a completely understandable approach for a work of this size. Engine insights do tend to disrupt the narrative by pointing out large numbers of mistakes in classic games, and somehow it fits the flow of the book better to hear what people thought about the games at the time. It does however mean that there is still a further story to be told about Stahlberg’s games, as they have many more twists and turns than is apparent from the contemporary annotations. I’m preparing a video series on some of his most notable games so you can judge for yourselves if you are interested!

Holmgren has also done a fantastic job of tracing so many of Stahlberg’s games (including games played in local competitions or simultaneous displays) as well as many contemporary annotations, many by Stahlberg himself. It is worth noting that with the exception of a small number of games annotated by modern players, most of the games have not been computer-checked. I think that this is a completely understandable approach for a work of this size. Engine insights do tend to disrupt the narrative by pointing out large numbers of mistakes in classic games, and somehow it fits the flow of the book better to hear what people thought about the games at the time. It does however mean that there is still a further story to be told about Stahlberg’s games, as they have many more twists and turns than is apparent from the contemporary annotations. I’m preparing a video series on some of his most notable games so you can judge for yourselves if you are interested!

This period of chess history before the Second World War has always been my favourite: so much seemed possible in chess, you could still discover so much! It was funny to see how many ‘Swedish Variations’ were introduced during this time.

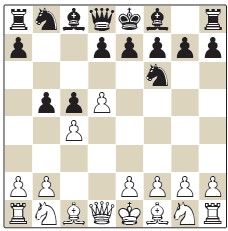

The Swedish Defence in the Tarrasch:

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.♘c3 c5 4.cxd5 exd5 5.♘f3 ♘c6 6.g3 c4 with the follow-up ...♗b4 and ...♘ge7 was an invention of Stoltz and got its first major test at the 1933 Folkestone Olympiad, netting the Swedish team ten wins (most notably for Stahlberg against Sultan Khan and for Lundin against Reuben Fine), four draws and one loss (unfortunately our hero’s responsibility!).

with the follow-up ...♗b4 and ...♘ge7 was an invention of Stoltz and got its first major test at the 1933 Folkestone Olympiad, netting the Swedish team ten wins (most notably for Stahlberg against Sultan Khan and for Lundin against Reuben Fine), four draws and one loss (unfortunately our hero’s responsibility!).

Then there was the Swedish Meran:

1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.♘f3 ♘f6 4.♘c3 e6 5.e3 ♘bd7 6.♗d3 dxc4 7.♗xc4 b5 8.♗d3 b4 which was pioneered by Erik Lundin and netted some good victories in the Warsaw and Munich Olympiads.

which was pioneered by Erik Lundin and netted some good victories in the Warsaw and Munich Olympiads.

Finally there is this beauty: which we of course know as the Benko Gambit (or Volga gambit, if you want to annoy Benko!) but is apparently known in Sweden as the Kaijser Gambit after the Swedish player Fritz Kaijser (1908-1983), who analysed this line in the 1940s! I also have to mention that the first known game in this opening is Stahlberg-Stoltz, Stockholm 1933!

which we of course know as the Benko Gambit (or Volga gambit, if you want to annoy Benko!) but is apparently known in Sweden as the Kaijser Gambit after the Swedish player Fritz Kaijser (1908-1983), who analysed this line in the 1940s! I also have to mention that the first known game in this opening is Stahlberg-Stoltz, Stockholm 1933!

I’ve lost track of the number of rabbit holes I’ve dived into because of the fascinating detail in this book. I even ended up reading the dystopian 1940s Swedish novel Kallocain, because the author (Karin Boye) apparently stayed in the same apartment block as Stahlberg!

This is a stunning book and the only real downside to it is that we may have to wait a couple of more years for the second volume – covering Stahlberg’s time in Argentina after the Second World War – to appear! Can’t wait! 5 stars!

We finish with the book I read first this month: The Real Paul Morphy by Charles Hertan (New In Chess). Do I have a problem with great American players? I don’t think so, but just as I always sigh inwardly when seeing yet another Fischer book (in all fairness, there are a lot!), I tend to have the same reaction with Paul Morphy. Perhaps for Morphy it’s rooted in something a grandmaster colleague once said to me about Morphy’s games: ‘There are so many odds games – hopeless!’ However, since watching Leela take on the world at odds chess I’ve definitely revised my previous opinion of odds play and that has definitely raised my appreciation of Morphy’s skill. I also discovered through this book that it’s important to have a good guide to Morphy’s life and games. In these days of 13-year old grandmasters and 18-year-old World Championship Challengers the plain story of Morphy’s emergence seems somehow less remarkable. However, when you see his career unfold within the context of (chess) life at that time, you really do understand why he made such an impact and why his name still resonates today.

We finish with the book I read first this month: The Real Paul Morphy by Charles Hertan (New In Chess). Do I have a problem with great American players? I don’t think so, but just as I always sigh inwardly when seeing yet another Fischer book (in all fairness, there are a lot!), I tend to have the same reaction with Paul Morphy. Perhaps for Morphy it’s rooted in something a grandmaster colleague once said to me about Morphy’s games: ‘There are so many odds games – hopeless!’ However, since watching Leela take on the world at odds chess I’ve definitely revised my previous opinion of odds play and that has definitely raised my appreciation of Morphy’s skill. I also discovered through this book that it’s important to have a good guide to Morphy’s life and games. In these days of 13-year old grandmasters and 18-year-old World Championship Challengers the plain story of Morphy’s emergence seems somehow less remarkable. However, when you see his career unfold within the context of (chess) life at that time, you really do understand why he made such an impact and why his name still resonates today. Hertan starts by sketching a picture of the state of chess before Morphy arrived (plenty of Adolf Anderssen Evans Gambit games!) and then moves on to biographical information about Morphy’s ancestors (very colourful!). We have a chapter on Morphy’s youthful games before a brief summary of Morphy’s career at college (he was by all accounts a very fine student). And then we start on Morphy’s ascent to the top of the Chess Olympus with the American Chess Congress of 1857 which he won by defeating an excruciatingly slowmoving Louis Paulsen +5 -1 =1 in the final. One thing I hadn’t realised was that one of my favourite Morphy games (against Louis Paulsen) was played in a blindfold simultaneous display in which Paulsen played four blindfold games with Paul also playing blindfold! I first saw this game in the excellent Winning Chess Manoeuvres by Guliev where he posited this game as the forerunner to Fischer’s famous Hedgehog attack against Ulf Andersson in Siegen 1970.

Hertan starts by sketching a picture of the state of chess before Morphy arrived (plenty of Adolf Anderssen Evans Gambit games!) and then moves on to biographical information about Morphy’s ancestors (very colourful!). We have a chapter on Morphy’s youthful games before a brief summary of Morphy’s career at college (he was by all accounts a very fine student). And then we start on Morphy’s ascent to the top of the Chess Olympus with the American Chess Congress of 1857 which he won by defeating an excruciatingly slowmoving Louis Paulsen +5 -1 =1 in the final. One thing I hadn’t realised was that one of my favourite Morphy games (against Louis Paulsen) was played in a blindfold simultaneous display in which Paulsen played four blindfold games with Paul also playing blindfold! I first saw this game in the excellent Winning Chess Manoeuvres by Guliev where he posited this game as the forerunner to Fischer’s famous Hedgehog attack against Ulf Andersson in Siegen 1970.

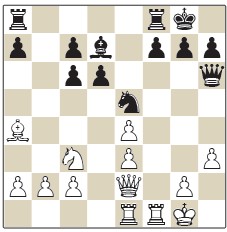

Louis Paulsen

Paul Morphy

New York, blindfold simul 1857

1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♘c3 ♗c5 4.♗b5 d6 5.d4 exd4 6.♘xd4 ♗d7 7.♘xc6 bxc6 8.♗a4 ♕f6 9.0-0 ♘e7 10.♗e3 ♗xe3 11.fxe3 ♕h6 12.♕d3 ♘g6 13.♖ae1 ♘e5 14.♕e2 0-0 15.h3 Paulsen has played quite poorly (well, he was playing blindfold!) but Morphy’s solution is still stunning (and he was blindfold too!).

Paulsen has played quite poorly (well, he was playing blindfold!) but Morphy’s solution is still stunning (and he was blindfold too!).

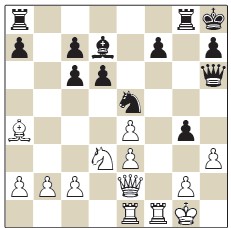

15...♔h8 16.♘d1 g5 17.♘f2 ♖g8 18.♘d3 g4 Power play! 19.♘xe5 dxe5 20.hxg4 ♗xg4 21.♕f2 ♖g6 22.♕xf7 ♗e6 23.♕xc7 ♖xg2+ 24.♔xg2 ♕h3+ 25.♔f2 ♕h2+ 26.♔f3 ♖f8+ 27.♕f7 ♖xf7 Mate.

19.♘xe5 dxe5 20.hxg4 ♗xg4 21.♕f2 ♖g6 22.♕xf7 ♗e6 23.♕xc7 ♖xg2+ 24.♔xg2 ♕h3+ 25.♔f2 ♕h2+ 26.♔f3 ♖f8+ 27.♕f7 ♖xf7 Mate.

The next chapter deals with Morphy’s adventures in Europe, which were compressed into a little less than a year (June 20th 1858 to April 30th 1859), with the decisive +7 -2 =2 victory over Adolf Anderssen the absolute pinnacle. Hertan concludes with Morphy’s life after his return to America, which triggered his retirement from chess and a seeming descent into mental illness.

Perhaps the only thing that somewhat confused me was the author’s use of the Fritz 18 engine to analyse the games. Fritz 18 is of course way stronger than any human player and will do a perfectly decent job, but it’s an average-strength engine in the general scheme of things, It just seems strange to ignore any of the much stronger open-source (free!) engines available like Stockfish or Leela.

However, I really enjoyed this book a lot! Sometimes you really need someone to take you by the hand and really show you and explain to you the qualities of a certain book, or piece of music or chess player and Hertan did exactly this for me with Morphy! 5 stars! ■