How to review your game

The advise is quite simple. Learn from your mistakes, and identify your mistakes by reviewing your games. But how do you do that? These five steps will help: start writing, zoom in, zoom out, consult a friend or coach, and only then start the engines.

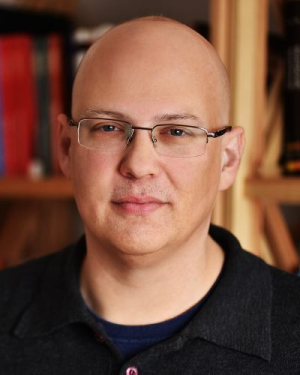

by Nate Solon

*** This column appeared in New In Chess magazine 2024#1. Please let us know what you think of this new column. ***

Chess is hard. It’s hard to find the best moves with your clock ticking and your opponent breathing down your neck. It’s also hard to find the best moves at home, with a coffee, with unlimited time. Maybe not quite as hard, but still really hard!

For this reason the age-old advice to review your games, while undoubtedly good, could also use some elaboration. How, exactly, should you approach the review process to get as much as you can out of it?

Start by recording your thoughts

This is my first suggestion because it’s something players of all levels can do. You don’t need to correctly analyze every possibility, just write down as much as you can remember about what you were thinking during the game: variations you considered, how you evaluated positions, what you were afraid of, and so on. Crucially, include feelings as well as thoughts, because for many players emotional hang-ups are more relevant blockers than lack of knowledge. If I had a dollar for every time someone played h3 because they were once traumatized by a knight on g4, I could safely retire!

Having this record of your thoughts will be a valuable resource for any further exploration you do on the game, whether it’s on your own, with a friend or coach, or with the engine. The reason to do it first is that outside influences have a way of crowding out your own thoughts, especially the engine (we’ll get to that later). Ultimately, game review isn’t about what you should have played in the last game, it’s about how you can play the next game better, and that means improving your thought process. You can think of this step as creating an augmented score sheet: the traditional score records the moves, now you are adding the thoughts.

Having this record of your thoughts will be a valuable resource for any further exploration you do on the game, whether it’s on your own, with a friend or coach, or with the engine. The reason to do it first is that outside influences have a way of crowding out your own thoughts, especially the engine (we’ll get to that later). Ultimately, game review isn’t about what you should have played in the last game, it’s about how you can play the next game better, and that means improving your thought process. You can think of this step as creating an augmented score sheet: the traditional score records the moves, now you are adding the thoughts.

It’s a good idea to do this step as soon as possible after the game, as long as it doesn’t interfere with your performance in the tournament, because memories of what happened during the game tend to fade quickly. I like to write down my thoughts while I enter the moves from my score sheets into my games database. By the way, make sure to save all your tournament games in one place. You can use a Chessbase file, Lichess study, or Chess.com library. Either way, it’s a great resource for tracking your growth, or just reminiscing about past games. Your future self will thank you.

One tip: the more honest you can be about your real thoughts during the game, the better your chances of getting better. I have a friend, another chess coach, who told me he can tell in the first lesson how likely a student is to improve by how honest they are about their mistakes. Those who admit their mistakes frankly and directly are likely to improve; those who obfuscate or make excuses often struggle.

At first it seemed incredible that he could predict improvement from this factor alone, but there is a logic to it. Mistakes are your best clues as to what you need to work on, so if you ignore or misrepresent them, you aren’t doing yourself any favors. Admitting you made a silly mistake might not feel good in the moment, but will actually help you improve in the long run. At the same time, do not be excessively harsh with yourself; after all, everyone makes mistakes. Just note your thoughts in a matter-of-fact way and adjust as necessary where you went wrong.

At first it seemed incredible that he could predict improvement from this factor alone, but there is a logic to it. Mistakes are your best clues as to what you need to work on, so if you ignore or misrepresent them, you aren’t doing yourself any favors. Admitting you made a silly mistake might not feel good in the moment, but will actually help you improve in the long run. At the same time, do not be excessively harsh with yourself; after all, everyone makes mistakes. Just note your thoughts in a matter-of-fact way and adjust as necessary where you went wrong.

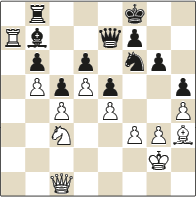

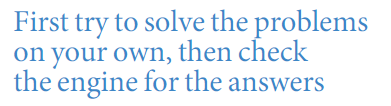

For example, in this position I had as White against Graham Horobetz, I wrote in my notes that I did not feel nearly as confident as I should have, given how good my position was. I agreed to a draw several moves later after a mistake that squandered some of my advantage. I realized I had missed an opportunity in this game.

For example, in this position I had as White against Graham Horobetz, I wrote in my notes that I did not feel nearly as confident as I should have, given how good my position was. I agreed to a draw several moves later after a mistake that squandered some of my advantage. I realized I had missed an opportunity in this game.

Zoom in

If analyzing the whole game feels unmanageable, focus on one moment. You probably already have a moment in mind. The sacrifice that looked promising, but you were scared to go for. The exchange you didn’t know how to evaluate. The pawn structure you had never seen before. Whatever position most stands out to you from the game, go deep on that moment. Try out some different lines on the board and see if you can gain a deeper understanding of what was going on. As always, capture your conclusions with notes.

In the position above, I would ask some questions like, Does ♕h6+ lead anywhere? What about the pawn breaks – how do f4 or g4 play out? Can I arrange my pieces to make these breaks more effective? What about Black – does he have any active ideas, or just have to wait passively? By playing out some lines on the board I can start to get a better handle on these ideas.

Zoom out

Analyzing any position thoroughly usually reveals hidden depths, but when it comes to practical improvements in my play, I find the biggest insights come from comparing across games. For this reason, in addition to my database with all my games, I like to keep a leaner document with only the most important details. For each game, I include a few basic pieces of information: color, opening, opponent, and opponent’s rating. Most importantly, I write the single biggest factor that decided the game. For example, ‘I forgot my prep and got a losing position from the opening,’ or, ‘I spent too much time on on-critical positions early on, then didn’t have enough time to calculate properly when the position got sharp.’ This can be done in a basic document or spreadsheet app like Word or Google Sheets.

When you do this, you often start to see obvious patterns that you were blind to when you only analyzed your games one at a time. It’s not uncommon to find that most or all of your recent losses really came down to variations on the same mistake.

When you do this, you often start to see obvious patterns that you were blind to when you only analyzed your games one at a time. It’s not uncommon to find that most or all of your recent losses really came down to variations on the same mistake.

After reviewing this game, I noticed a pattern that I am often uncomfortable or nervous when objectively the game is going well for me. It sounds paradoxical, but I’ve noticed this is in fact a common issue for many players. Perhaps knowing you have the advantage creates psychological pressure to get the full point. But being a bit more relaxed and confident is not only more fun, it is also a better way of pressing the advantage. The truth is that White has all the chances in this position, so really, my opponent is the one who should be nervous. A good practical strategy in such a situation is to shuffle around, make the opponent guess your intentions, and deplete their clock time before changing the position.

Don’t go it alone

Chess is an individual sport, but chess improvement is best played as a team game. Once you’ve recorded your own thoughts, one of the best things you can do is have a look at the game with someone else. If you have a coach, they are of course a great person to look at the game with. But looking at the game with a friend or training partner works well too. They don’t even have to be stronger than you, often it’s helpful just to have another pair of eyes.

If you do have access to a stronger player, find a critical moment (perhaps the one you used for the ‘zoom in’ section), and ask: ‘How would you think about this position?’I find this phrase often pulls out valuable insights, even from players who may not be highly skilled coaches or communicators. Remember, it is ultimately not about the moves you should have played last game, but how you should think about the next game, so a strong player’s thought process is often more eye-opening than the engine’s top line.

Save the engine for last

I am not an engine hater. Far from it: I consider the engine the single most important tool we have at our disposal as chess players. But this powerful tool needs to be treated with an appropriate amount of caution, because once you turn on the engine, it’s all too easy to turn off your own brain. This is one of the reasons I recommend writing down the thoughts you had during the game as the first step. Once you are influenced by outside opinions, especially those of the engine, it becomes very difficult to accurately reconstruct what you were thinking during the game. You can’t unsee what the engine has shown you.

What, then, is the value of the engine? Simply put, it tells you the right answers. Yes, I know it’s still possible to find some weird corner case positions that the engine doesn’t entirely understand, but in any normal position it is far stronger than any human, so it is safe to assume the engine is right. The bigger challenge is understanding what it says in a way that’s relevant for your own game.

The combination of struggling with a position on your own, and then looking at the engine analysis, is far more powerful than either in isolation. It’s somewhat as though you’re taking a practice test in school. Looking at the answer key without attempting to first answer the questions yourself probably wouldn’t be very helpful. Working through the problems on your own without the answers would be better. But the best approach would clearly be to first attempt the problems on your own, then compare your solutions to the answer key. Then you can see where you went wrong and address any mistakes in your process.

The combination of struggling with a position on your own, and then looking at the engine analysis, is far more powerful than either in isolation. It’s somewhat as though you’re taking a practice test in school. Looking at the answer key without attempting to first answer the questions yourself probably wouldn’t be very helpful. Working through the problems on your own without the answers would be better. But the best approach would clearly be to first attempt the problems on your own, then compare your solutions to the answer key. Then you can see where you went wrong and address any mistakes in your process.

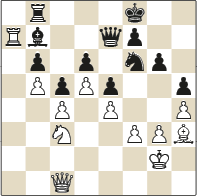

When I fed this position to the engine, it came up with an insane forced win.

When I fed this position to the engine, it came up with an insane forced win.

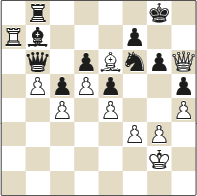

38.♕h6+ ♔g8 39.♘a4 ♕c7 40.♘xb6! ♕xb6 41.♗e6!.

White ignores the hanging rook and offers a bishop as well! The point is that Black has no way now to prevent ♕xg6.

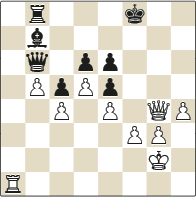

41...fxe6 (41...♕xa7 42.♕xg6+ leads to a forced mate) 42.♕xg6+ ♔h8 43.♕xf6+ ♔h7 44.♕f7+ ♔h8 45.♕xh5+ ♔g7 46.♕g4+ ♔f8 47.♖a1.

41...fxe6 (41...♕xa7 42.♕xg6+ leads to a forced mate) 42.♕xg6+ ♔h8 43.♕xf6+ ♔h7 44.♕f7+ ♔h8 45.♕xh5+ ♔g7 46.♕g4+ ♔f8 47.♖a1.

White emerges with three pawns for the bishop. Materially speaking it’s close to equal, but Black’s bishop is restricted, his king is open, and White has connected passed pawns. Taken together it adds up to a winning position for White.

White emerges with three pawns for the bishop. Materially speaking it’s close to equal, but Black’s bishop is restricted, his king is open, and White has connected passed pawns. Taken together it adds up to a winning position for White.

What should I take from this? Well, it would have been very difficult to spot and go for this multiple piece sacrifice in a position where I seemed to have a stable advantage. Even the final position is not easy to evaluate from a distance. So this is not the type of line I would really expect myself to see, although I can certainly enjoy the engine’s ingenuity. But it is a good reminder that surprising combinations can be possible when the opponent’s pieces are very restricted, and the motif with ♗e6 is worth remembering. But my bigger takeaway would be that the engine sees a big advantage for White after virtually any move, and in such a position I need to remain calm, and continue to apply pressure on my opponent to secure a win.

Conclusion

Above all, use game review to cultivate your curiosity. Let it be your guide as to which parts of the game to explore more deeply. And if there is no part of the game you’re curious about, take it as an opportunity to become more curious. That, like tactics and strategy, is something you can work on. ■

How to review a blitz game

To quickly review a blitz game, you can use my OBIT system.

- Opening

I start with reviewing the opening phase and updating my opening files to the first move I would have played differently. - Blunders

Review any blunders and make sure you understand them. - Interesting moment

That is the same as the ‘zoom in’ of the long review. Follow your curiosity! - Takeaway

Write down one key takeaway from the game. And look for patterns across games.

One thing that could have been done to improve the article was to have one or two more examples used to illustrate a concept. For example, in the Zoom In section it would have been helpful to see a possible sample game so I can see how a person might come up with variations. At my level, 1000, I find coming up with variations hard and deciding what the opponent would have played in the variation even more difficult.

I am not a big fan of the computer for reviewing my games because of my level. Some players would get a lot out of it. However, I found it long and therefore put more emphasis on the engine.

Reading this article helped me more than any article on reviewing the game. Its focus was also somewhat different than other articles. Rather than focus on smaller specific things a player could do, it communicated the rationale behind a review. The article did a good job of discussing the big picture of a game review. This will help me do a better job since it will help put me in the right mindset and make me understand the review is my chance to use my mind to understand how I play and see where I need to make improvements.