Robert Hübner (1948-2025) A great player and a unique mind

The news of the death of Robert Hübner, yesterday at the age of 76, after a long illness, filled me with great sadness. I remembered how we met at tournaments and at our homes, our conversations about serious and light-hearted matters, letters that we exchanged. The profundity of his thoughts and his great sense of humor.

How, at breakfast during a tournament, he almost fell off his chair when I told him about a work of art by Joseph Beuys - the artist stroking a dead hare in his lap – entitled Wie man den toten Hasen die Bilder erklärt (How to explain pictures to a dead hare). How, at another breakfast, I found him reading a book and asked what he was reading. He said that he had started rereading Plato (in Greek, of course) and I teasingly wondered, ‘Is it any good?’ To which he matter-of-factly replied: ‘I don’t think much has been added after Plato.’

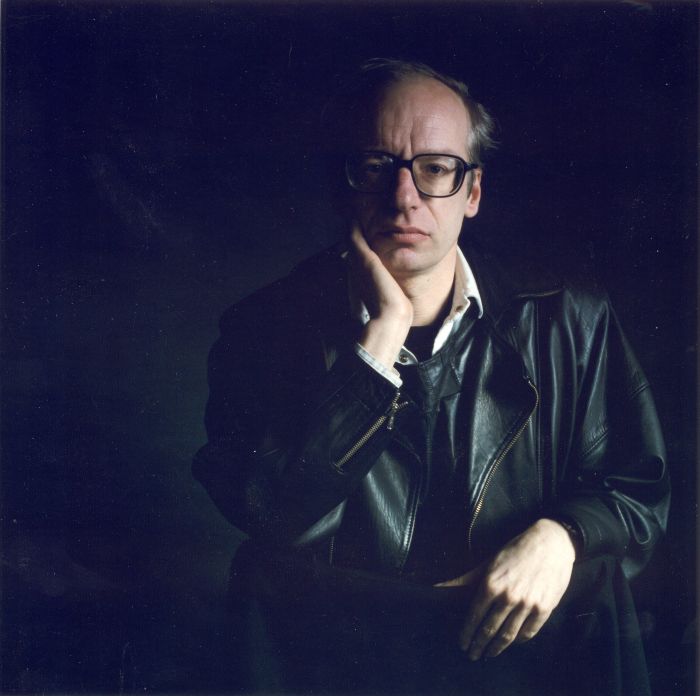

Robert Hübner: ‘You cannot read this book, on which I have worked for four thousand hours, in five minutes, that much is clear.’ (photo: Gerard de Graaf)

Robert Hübner: ‘You cannot read this book, on which I have worked for four thousand hours, in five minutes, that much is clear.’ (photo: Gerard de Graaf)

We spoke Dutch, one of a good number of languages he spoke fluently. One of his favourite Dutch writers was Marten Toonder, a brilliant comic strip creator, whose tales about Olivier B. Bommel he found both brilliant and extremely funny. Having just finished one of Toonder’s books, he once wrote me a letter saying he had greatly enjoyed it, but that there were three words that he failed to grasp; clearly his command of the Dutch language was lacking. I could reassure him that all three words didn’t exist and had been fabricated by the author.

His exceptional language skills regularly led to exaggerations as to the number of languages he spoke. No, he couldn’t speak or read 22 languages, as I saw somewhere, but a dozen seems a fair guess. And no, he didn’t learn Finnish in one or two days so he could converse with Heiki Westerinen, but studied the language for years to reach an acceptable level (in his own eyes).

Just like he made a serious and deep study of everything that fascinated him. Acquiring knowledge and insight takes a lot of time and effort, there are no shortcuts. When I asked him if dedicating 400 pages to 25 annotated games (as he did) wasn’t asking a bit much of the reader, he simply replied: ‘You cannot read this book, on which I have worked for four thousand hours, in five minutes, that much is clear. Indeed, you have to have the wish to delve into the structure of the game. The reader has to be co-operative. I think that a rather weak player can learn a lot from this analysis too. But he’ll have to work, as I had to work.’

This quote is from the interview that I had with Robert Hübner in 1997. At that point he had not spoken to the press for 16 years and I was delighted that I had managed to persuade him with an offer that apparently he could not refuse. I had invited him to come to The Hague for three days and suggested the following schedule: each day I would interview him for one hour and then we’d go to a museum, and in the evening we would have dinner and talk some more. They were three wonderful days and my then wife summed them up perfectly after Robert had left: ‘He, he is welcome to come back any time.’

Robert Hübner’s chess career was rich and long. For decades he was Germany’s strongest grandmaster and between 1971 and 1988 he permanently belonged to the world’s top 20. His highest ranking in the FIDE rating list was 3rd place in 1981.

For his remarkable adventures in the Candidates matches of the world championship cycle and his many other chess highlights, I gladly refer to his Wikipedia page and the obituaries that have appeared. Here I would like to pay tribute to a great chess player and an inspiring thinker with the interview we had in 1997, and which appeared both in New In Chess (1997/2) and in the Dutch weekly Vrij Nederland. When I reread it today, I was as touched and impressed by the clarity of his thinking and his attempt to be as honest as possible, as I was then.

Robert Hübner was one of a kind. I could quote from the interview endlessly, but I will limit myself to one quote: ‘Progress could be made if reason could gain supremacy over emotions.’

True then, and true today.

The other quotes are waiting for you in the complete interview.

So gerne ich das mit dem Übermenschenstatus überall gelesen habe, würde ich gerne wissen, wie er sich das alles angearbeitet hat. 4000 h an einem Buch zu arbeiten ist kaum nachvollziehbar. Noch dazu, wenn er (wohl witzelnd) behauptet hat, Schach sei nicht so wichtig, anderes gäbe ihm mehr.

The Quote "Progress could be made if reason could gain supremacy over emotions" may be true, but only would give sense to me if further explained.

Als ich klein war und mit Schach angefangen habe, war Hübner der beste Spieler in Deutschland und ständig in der Presse. Seine Partien. Ansonsten war das wenige (persönliche) was berichtet wurde: Sympathischer, aber komischer Kauz. Vlt. ist das ja richtig, vlt. aber auch nicht. Über den nach Lasker erfolgreichsten deutschen Schachspieler mehr als nur seine Partien zu erfahren, wäre auf jeden Fall für die Gemeinheit unglaublich interessant.