These book reviews by Matthew Sadler were published in New In Chess magazine 2025#1

In one of those chess books without chess in it, Peter Doggers manages to serve the contingent of new chess fans who started as Netflix watchers or YouTube subscribers. It is a worthy introduction to chess and the world behind it.

My youngest nephew received a SIM card for his phone for Christmas which has led to some late-night calls from him (don’t tell his parents) excitedly explaining the ins and outs of an esports game called Rocket League. It involves flying cars playing football, it’s played professionally, and the best player in the world is a Frenchman called Zen. My nephew hasn’t shown much interest in chess so far but after the chess.com announcement that chess would be included in the inaugural 2025 Olympic Esports Games (next to games like Rocket League), maybe I’ll jump in his esteem!

Announcements like this do make me feel my age. As a chess player raised in the pre-computer age, I’m firmly grounded in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Most of the positions I learnt chess from are linked to that era and most of my references and anecdotes are too!

Time to modernise then, and what better place to start than by reading The Chess Revolution by Peter Doggers? It’s one of those chess books without any chess in it! (until the Appendix). Peter is a well-known Dutch journalist who ran the Chess-Vibes website before it was acquired by chess.com for whom he now works.

Time to modernise then, and what better place to start than by reading The Chess Revolution by Peter Doggers? It’s one of those chess books without any chess in it! (until the Appendix). Peter is a well-known Dutch journalist who ran the Chess-Vibes website before it was acquired by chess.com for whom he now works.

Peter felt that amongst the vastness of chess literature, a book was missing ‘serving the contingent of new chess fans who’ve encountered the game as Netflix watchers or YouTube subscribers and are in desperate need of a good introduction to this sport and the world behind it’. Furthermore, Peter notes that ‘since the last book that attempted to cover the full history of chess was published in 1985, perhaps this one can bridge the gap with the modern era, collating chess’ past, present and future in one place and charting its relationship with culture and technology’.

In just over 400 pages, Doggers takes us through a quick overview of chess history (about 30 pages) and then cycles through topics such as chess in movies, literature, art and theatre, chess and science and the best players of all time (Fischer, Garry and Magnus). This takes up about a third of the book. The last two-thirds are dedicated to various facets of the computer and Internet revolution: the advent of engines (with a whole chapter on cheating and the Carlsen-Niemann saga), chess websites (one chapter is entitled ‘How chess.com, came, saw and conquered’) and streaming. It’s a well-written and easily readable book and I could easily imagine myself as a child fresh to chess spending many happy hours leafing through it. The book relates plenty of timeless anecdotes and stories while also discussing modern chess personalities whose names a new chess player is likely to have come across (much more so than Lasker or Capablanca!). That makes a lot of sense of course considering the target audience Peter was aiming for.

It’s a well-written and easily readable book and I could easily imagine myself as a child fresh to chess spending many happy hours leafing through it. The book relates plenty of timeless anecdotes and stories while also discussing modern chess personalities whose names a new chess player is likely to have come across (much more so than Lasker or Capablanca!). That makes a lot of sense of course considering the target audience Peter was aiming for.

Just a few things struck me while reading it. To me, the enormous increase in strength of countries like India (the most prominent, of course, but there are many more), coupled with a significant decrease in the chess strength of Russia, has been one of the most remarkable changes of the past ten to fifteen years. For someone whose chess journey started in the 1980s, it’s pinch-yourself-to-make-sure-you’reawake territory to look at tournament standings and be surprised if a Russian player is at the top (let alone three as in the World Rapid!).

I may have missed something, but I only noticed the Indian chess boom mentioned in a brief paragraph about Chessbase India’s YouTube channel. The upcoming (when the book was written) World Championship match between Ding and Gukesh is mentioned in just one brief sentence. When you compare that to the multiple chapters on chess.com and streaming, it made me reflect – a little tearfully perhaps – on where chess is going from here and wonder when I’ll lose the feeling of being connected to the modern chess world. I had assumed that all the work I do with engines would keep me ‘modern’, and from the pure chess perspective, it certainly helps a lot.

However, as the book shows there’s more to chess nowadays than just the chess! There is a massive influx of new, young players who have learnt the game in a way completely different from mine and whose frames of reference have little in common with mine. Brought up as I was on a regular,

slow trickle of ‘important’ classical events, the sheer volume of strong online rapid and blitz events confuses me but it matches the entertainment expectations of this new generation. At the top level, there’s lots of fantastic chess played, but it gets harder to spot it when so much is happening all the time! Even Freestyle Chess – which I like a lot in principle – worries me because I have to throw away so much of what I’ve learnt to play it! (I don’t even think control of the centre is that important without the standard piece setup.) None of these are objective criticisms of the book of course – merely the lament of someone who’s suddenly realised he won’t stay young forever... and maybe isn’t that young already!

All in all, however, I definitely think that Peter achieved the goals he set for himself with the book, and I’d happily recommend it as a present for a player new to chess who is looking to dive a little deeper into the modern chess world in an easily accessible and relatable manner. 4 stars!

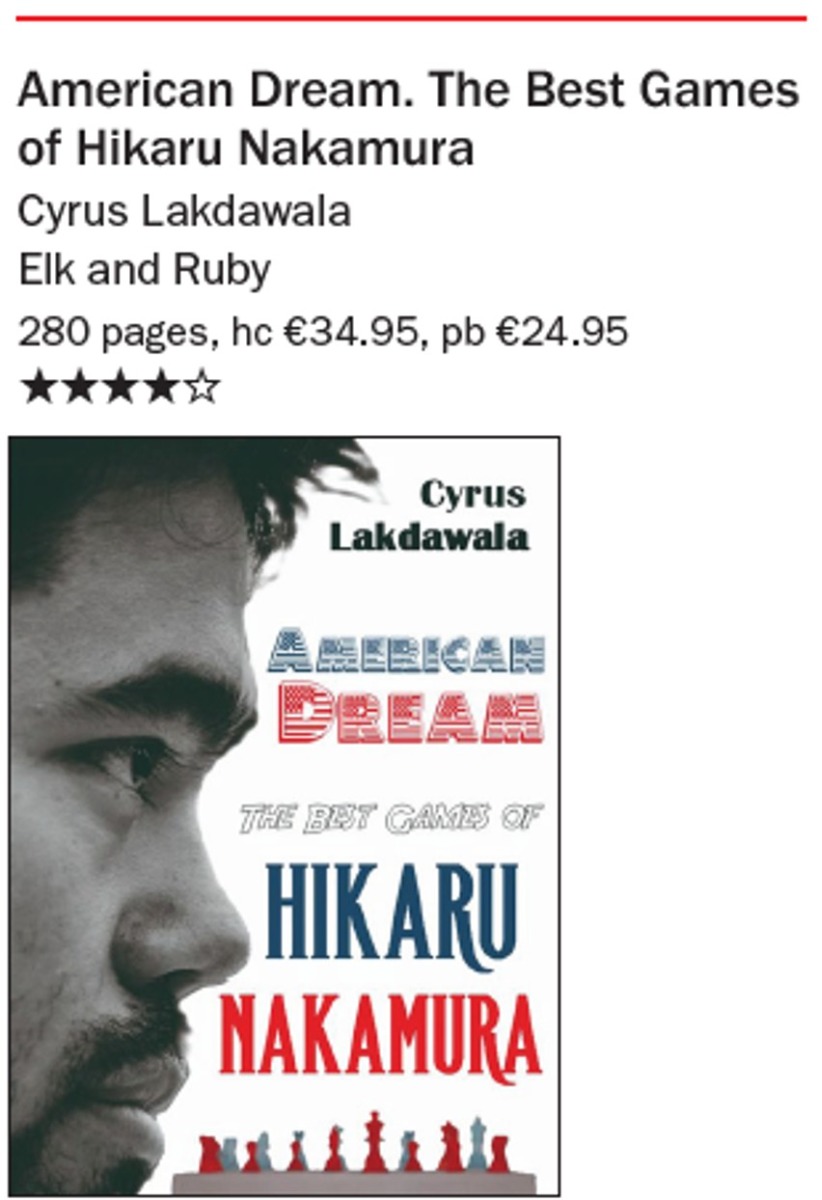

There is of course a clear link between The Chess Revolution and the ever-prolific Cyrus Lakdawala’s American Dream. The Best Games of Hikaru Nakamura, one of chess.com’s most eminent streamers, Hikaru is central to the latter chapters of The Chess Revolution. As much of chess activity moves to online events, I’ve become conscious that my knowledge of the best games and the styles of the world’s top players is getting really hazy. It also doesn’t help that everyone plays virtually every opening – good, bad or indifferent – so you’re never sure what they actually like playing! That’s where a Best Games collection still has great value, spotlighting key games and highlighting stylistic traits over a whole career. I’ve recently enjoyed Best Games collections of Fabiano Caruana and Ding Liren and now you can add one extra to the list! Probably (too) heavily influenced by his renowned blitz prowess, I’d automatically categorised Hikaru as a ‘winning ugly’ type of player: the sort of player who simply has the knack for getting things done. It turns out that this is yet another of my lazy generalisations that needs correction because the games in this collection are simply stunning!

There is of course a clear link between The Chess Revolution and the ever-prolific Cyrus Lakdawala’s American Dream. The Best Games of Hikaru Nakamura, one of chess.com’s most eminent streamers, Hikaru is central to the latter chapters of The Chess Revolution. As much of chess activity moves to online events, I’ve become conscious that my knowledge of the best games and the styles of the world’s top players is getting really hazy. It also doesn’t help that everyone plays virtually every opening – good, bad or indifferent – so you’re never sure what they actually like playing! That’s where a Best Games collection still has great value, spotlighting key games and highlighting stylistic traits over a whole career. I’ve recently enjoyed Best Games collections of Fabiano Caruana and Ding Liren and now you can add one extra to the list! Probably (too) heavily influenced by his renowned blitz prowess, I’d automatically categorised Hikaru as a ‘winning ugly’ type of player: the sort of player who simply has the knack for getting things done. It turns out that this is yet another of my lazy generalisations that needs correction because the games in this collection are simply stunning! Perhaps the most impressive aspect of the best modern players is their sheer versatility. Powerful attacks, speculative sacrifices, last-ditch defences, smooth technical performances – you see them all, and all against the strongest players in the world! This 277-page book contains 72 of Nakamura’s games, organised into thematic chapters such as ‘On the Attack’, ‘Defence and Counterattack’ and ‘The Dark Side of the Moon – Chaos and the Dynamic Element’, which is also the largest one! Lakdawala annotates in his typical chatty fashion which works well for this all-action selection! I could select pretty much any of the 72 games to show you but let’s embrace modernity and go for a crazy rapid game, played in 2024.

Perhaps the most impressive aspect of the best modern players is their sheer versatility. Powerful attacks, speculative sacrifices, last-ditch defences, smooth technical performances – you see them all, and all against the strongest players in the world! This 277-page book contains 72 of Nakamura’s games, organised into thematic chapters such as ‘On the Attack’, ‘Defence and Counterattack’ and ‘The Dark Side of the Moon – Chaos and the Dynamic Element’, which is also the largest one! Lakdawala annotates in his typical chatty fashion which works well for this all-action selection! I could select pretty much any of the 72 games to show you but let’s embrace modernity and go for a crazy rapid game, played in 2024.

Hikaru Nakamura

Fabiano Caruana

St. Louis Rapid 2024

Ruy Lopez

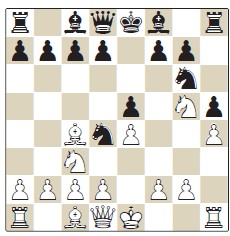

1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗b5 ♘ge7

There’s only one game of Fabiano’s in the database so this must have come as a surprise. Actually, this is also the only game of Hikaru’s as White in this line.

4.♘c3 ♘g6

4...g6 is another development scheme but I had some fun back in 2014 against this: 5.h4 h5 6.d4 exd4 7.♘d5 ♘xd5 8.exd5 ♕e7+ 9.♔f1 ♘e5 10.♗g5 f6 11.♘xe5 ♕xe5 12.♕d3 ♔f7 13.♖e1 ♕d6 14.♖h3 ♗g7 15.♖f3 a6 16.♗c4 b5 17.♗b3 ♗b7 18.♗f4 ♕c5 19.d6+ ♗d5 20.♖e7+. Aaah, the sort of game that made me happy I added 1.e4 to my repertoire! 1-0 Sadler-Cawley, Blackpool 2014.

5.h4 ♘d4

You’d think this is a fairly random offbeat line but there are over fifty games in the database, many of them high-level!

6.♗c4

6.h5 is played more often as pointed out by Lakdawala but the engines prefer 6.♗c4 slightly.

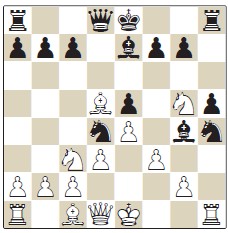

6...h5 7.♘g5 7...d5

7...d5

‘Forced’, says Lakdawala, but that’s not completely true.

7...♘e6 is also playable, but the text is much more challenging. It actually contains real venom, as White has only 1 move to maintain a better game: everything else is already better for Black!

8.♗xd5

8.♘xd5 (never played) is the engine recommendation pointed out by Lakdawala. After the text, White is in serious trouble!

8...♗g4 9.f3 ♘xh4 10.d3

10.♘xf7 ♕f6 or first 10...♘xg2+ followed by 11...♕f6 as recommended by Lakdawala is terrible for White. That was the key advantage of 8.♘xd5 which covers f6 and prevents the black queen from joining in the attack.

10...♗e7 Both sides are following a narrow path: this is Black’s only viable line but it’s winning!

Both sides are following a narrow path: this is Black’s only viable line but it’s winning!

11.♗xf7+

A new move and the toughest defence.

11.♘xf7 is natural, but surprisingly allows the black queen to activate itself after 11...♘hxf3+ 12.gxf3 ♗h4+ 13.♔d2 ♕f6 (threatening ...♕f4 mate) 14.♘e2 ♘xf3+ 15.♔c3 ♘d4 16.♖xh4 ♘xe2+ 17.♕xe2 ♗xe2 18.♖h2 ♖f8 19.♖xe2 ♕f1 20.♖h2 c6 21.♗e6 ♖xf7 22.♗xf7+ ♔xf7 23.♖xh5 ♔g8 24.♖f5 ♕g1 25.♖xe5 c5 0-1, Cheparinov-Shevchenko, Germany 2024.

11...♔d7

How can this be the wrong choice?

11...♔f8 was winning for Black. The pressure on the f7-bishop restricts White’s options but you need to be a special type of crazy – or rather a special type of prepared – to understand that White’s subsequent discovered checks achieve little! 12.0-0 ♗xg5 13.fxg4 ♗xc1 14.♕xc1 hxg4 15.♗h5+ (15.♗c4+ ♘hf3+ is the key resource 16.gxf3 ♕h4, with forced mate looming!) 15...♔g8 16.♗xg4 (16.♗f7+ ♔h7. Completely winning according to the engines but still ‘unclear’ to my 1980 pre-computer age eyes!) 16...♘xg2 17.♔xg2 ♕h4 is once again the key resource! An amazing counterattack!

12.fxg4 ♗xg5 13.gxh5 ♘xg2+ The players are still both balancing on a narrow tightrope. Now Hikaru makes another far-from-obvious misstep!

The players are still both balancing on a narrow tightrope. Now Hikaru makes another far-from-obvious misstep!

14.♔f2

14.♔f1 is pointed out by Lakdawala. Who would have thought that covering the e3-square with White’s king would make ...♘e3 more dangerous?

14...♘f4

14...♘e3 was a killer with the point that 15.♗xe3 ♗xe3+ 16.♔xe3 ♕g5+ 17.♔f2 ♖af8 leads to imminent mate. Caruana’s choice is weaker and now Hikaru steps up the power!

15.♕g4+ ♔d6 16.♗xf4 ♗xf4 17.♕xg7 c6 18.♖ag1 ♖h6 19.♗b3

Not the top engine move but good enough! The threat of ♕xb7 is difficult to meet.

19...b5 20.♘e2

‘The only piece not working in White’s army was his knight. Hikaru swaps it off for Black’s stronger one.’

20...♘xe2 21.♔xe2 ♔c5 22.c3 ♔b6 23.♖g6 ♖xg6 24.♕xg6 ♕d7 25.h6 ♖d8 26.♗d5

‘With this interference trick, Black’s attack morphs into a farce. Hikaru’s more aggressive move is better than the also winning, passive version with 26.♗c2.’

26...♔c7 27.h7 ♖h8 28.♗e6 ♕e7 29.♕f7 1-0.

A really nice collection of games that made me appreciate a great player and rediscover a host of games to which I hadn’t paid enough attention! The book is somewhere between 3 and 4 stars but we’ll bump it up to 4!

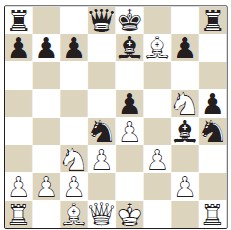

While streaming recently, I was asked whether I could name all the World Champions in order. I think I did pretty well on the Open World Champions but not so well on the Women’s World Champions (the order between Menchik and Gaprindashvili is quite tough to start with). If you’d asked me about FIDE Presidents, I’d have been totally clueless until Euwe. So when the author Henrik Malm Lindberg mailed me asking whether I’d be interested in reviewing his upcoming book about Folke Rogard, my first time-gaining thought was ‘Who?’ as I feverishly tried to recall whether Larsen had ever played any games against this lesser-known Danish master.

While streaming recently, I was asked whether I could name all the World Champions in order. I think I did pretty well on the Open World Champions but not so well on the Women’s World Champions (the order between Menchik and Gaprindashvili is quite tough to start with). If you’d asked me about FIDE Presidents, I’d have been totally clueless until Euwe. So when the author Henrik Malm Lindberg mailed me asking whether I’d be interested in reviewing his upcoming book about Folke Rogard, my first time-gaining thought was ‘Who?’ as I feverishly tried to recall whether Larsen had ever played any games against this lesser-known Danish master.

Well, he wasn’t Danish, and he hadn’t played against Larsen. He was, in fact, the Swedish lawyer who became FIDE President in 1949 until handing over to Max Euwe in 1970. FIDE President Folke Rogard traces his life from his early childhood in Stockholm, where a grammar school education led to law studies at Stockholm University and a prestigious career as a lawyer, through the FIDE Presidency to the end of his life where, perhaps exhausted from having combined two demanding professions, he withdrew more and more from his professional and social life.

Rogard became FIDE Vice-President in 1947 and two years later replaced the Dutch lawyer Alexander Rueb who had held the post from FIDE’s inception in 1924. What led Rogard to become FIDE President? Strangely enough, chess didn’t play a huge part in his childhood or youth though he had a peak of activity when he was aged between 18 and 21. He first came to prominence in Swedish chess when helping to organise the 1937 Stockholm Olympiad, also contributing a substantial sum to support the event. This led to the chairmanship of the Swedish Chess Federation. Similarly, Rogard’s instrumental role in making the 1948 Saltsjöbaden (Sweden) Interzonal take place propelled him to the top of the FIDE leadership. How interesting could the life of a FIDE President be? Really fascinating it turns out! I had wondered while reading The Chess Revolution whether Peter Doggers could have paid more attention to the current problems at FIDE (he mentions FIDE’s strong ties with Russia and its problematic leadership briefly in a few places) but reading this account, you sense that there is nothing really revolutionary about the current situation: we are witnessing the continuation of a power struggle that has been ongoing since the 1940s. From the moment he took office, Rogard was battling with a lopsided chess world in which one country owned most of the world’s strongest players and wished to exert a level of influence congruent with this status.

How interesting could the life of a FIDE President be? Really fascinating it turns out! I had wondered while reading The Chess Revolution whether Peter Doggers could have paid more attention to the current problems at FIDE (he mentions FIDE’s strong ties with Russia and its problematic leadership briefly in a few places) but reading this account, you sense that there is nothing really revolutionary about the current situation: we are witnessing the continuation of a power struggle that has been ongoing since the 1940s. From the moment he took office, Rogard was battling with a lopsided chess world in which one country owned most of the world’s strongest players and wished to exert a level of influence congruent with this status.

Despite FIDE’s ambitions to be the single official body for all chess-playing nations, it was extremely small in 1949 and chess federations across the world were impoverished after the end of the Second World War. It was a recurring nightmare to secure financial backing and ensure representative participation in FIDE events and for all his efforts, Rogard never managed to bind any lasting sponsors to the cause of chess. Perhaps the most striking facet of Rogard’s tenure is how little FIDE organisation existed and how much operated on the hero principle: Rogard kept FIDE afloat – and growing – by using extensive resources from his own law firm, and by regularly seeking help from the impressive social network that he had built up in his career.

I hadn’t expected to be so enthralled by this account, but I truly read this from cover to cover in one go. And the current chess situation starts to make a lot more sense when you understand how the important initial years of FIDE’s existence were shaped. Let’s award it 5 stars!

Elk and Ruby continue to explore the lesser-known areas of Soviet-era chess with Critical Theory: A Chess Biography of Isaac Lipnitsky. It’s really fascinating to learn something of the – often tragic – lives of the names of players you saw maybe once or twice in a tournament table of a Soviet Championship, often accompanied by the thought ‘Wow, he came equal 2nd in the 1950 Soviet Championship! How strong must he have been?’

Elk and Ruby continue to explore the lesser-known areas of Soviet-era chess with Critical Theory: A Chess Biography of Isaac Lipnitsky. It’s really fascinating to learn something of the – often tragic – lives of the names of players you saw maybe once or twice in a tournament table of a Soviet Championship, often accompanied by the thought ‘Wow, he came equal 2nd in the 1950 Soviet Championship! How strong must he have been?’

This exceptionally well-researched biography of 261 pages with a little over half dedicated to Lipnitsky’s games and writings, traces Lipnitsky’s career from childhood via an illustrious career in military intelligence during the Second World War to his discharge in 1947 and the fateful decision – taken in 1948 after abortive attempts to restart his university studies – to become a chess professional. Things didn’t go smoothly right away, but 1949 and 1950 were exceptional years, culminating in the aforementioned shared 2nd place in the 1950 Soviet Championship, just half a point behind Keres and ahead of Smyslov, Boleslavsky, Geller, Geller, Flohr, Petrosian and Averbach to name but a few! Somehow after that, things went awry for Lipnitsky. It is thought that the illness (most likely leukemia) that cost him his life tragically early in 1959 was already affecting his stamina and there was a severe reprimand (an editorial in Shakhmaty v SSSR magazine) attacking Lipnitsky’s ‘unacceptable’ behaviour at a tournament in Tbilisi in 1951. It is suspected that Lipnitsky may have sold some of his games to the weaker masters though there is no concrete evidence of this. In the 1950s, Lipnitsky also began to put more energy into writing and it was from that period that his magnum opus Questions of Modern Chess Theory (published by Quality Chess) arose. He died in 1959, aged just 35. Lipnitsky is best-known for an absolutely glorious tactical victory played in 1950 when he was at his peak. I don’t think I can avoid reproducing it here as a taster for many more interesting tactical skirmishes in the book!

Mikhail Beilin

Isaak Lipnitsky

Dzintari 1950

Queen’s Gambit, Ragozin Variation

1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 e6 3.♘c3 d5 4.♗g5 ♗b4

Lipnitsky’s Questions of Modern Chess Theory was originally intended as a monograph on the Ragozin Defence but mutated into something much bigger! It shows the affinity that he had with this opening.

5.♘f3 h6 6.♗xf6 ♕xf6 7.♕a4+ ♘c6 8.♘e5 ♗d7 9.♘xc6

Not really what White was aiming for but his original intention has a problem! The trap 9.♘xd7 ♕xd4 is pointed out by Lipnitsky.

9...♗xc3+ 10.bxc3 ♗xc6 11.♕b3 dxc4 12.♕xc4 0-0 13.f3 e5 14.d5 ♗d7 15.♕xc7

15.e4 c6 didn’t look pleasant to White (and it isn’t!) so he decides to grab the c-pawn and hope to survive the onslaught.

15...e4 16.♖c1

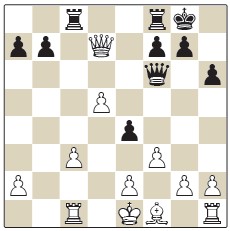

There are quite a few good moves for Black here, but Lipnitsky’s choice is beautiful.

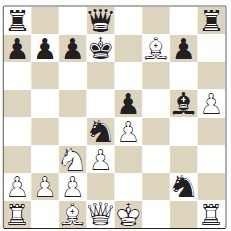

16...♖ac8 17.♕xd7 17...e3

17...e3

Nailing the white king to the e1-square while preparing to crash through on the c3-square.

18.♕a4

18.♕xb7 ♖xc3 19.♕b2 ♖fc8 20.♖xc3 ♖xc3 21.g3 ♖b3 is an attractive line given by Lipnitsky though the engines see 19...♖c5 as even stronger.

18...♖xc3 19.♖d1 ♖fc8 20.g3 ♖c1 21.♗h3

White is just about ready to castle but now Black is ready to strike!

21...♕c3+ 22.♔f1 ♖xd1+

22...♕d2 23.♗xc8 ♖xd1+ 24.♔g2 ♕xe2+ 25.♔h3 as pointed out by Lipnitsky is what White was hoping for. 25...♖xh1 26.♕e8+ ♔h7 27.♗f5+ with a quick mate.

23.♕xd1 ♕d2 24.♔g2 And now the move that really turns this game into a jewel!

And now the move that really turns this game into a jewel!

24...♖c1

0-1. (25.♕xc1 ♕xe2+ 26.♔g1 ♕f2 mate.)

A really interesting book shedding yet more light on this fascinating period of chess: 4 stars.

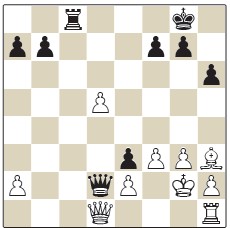

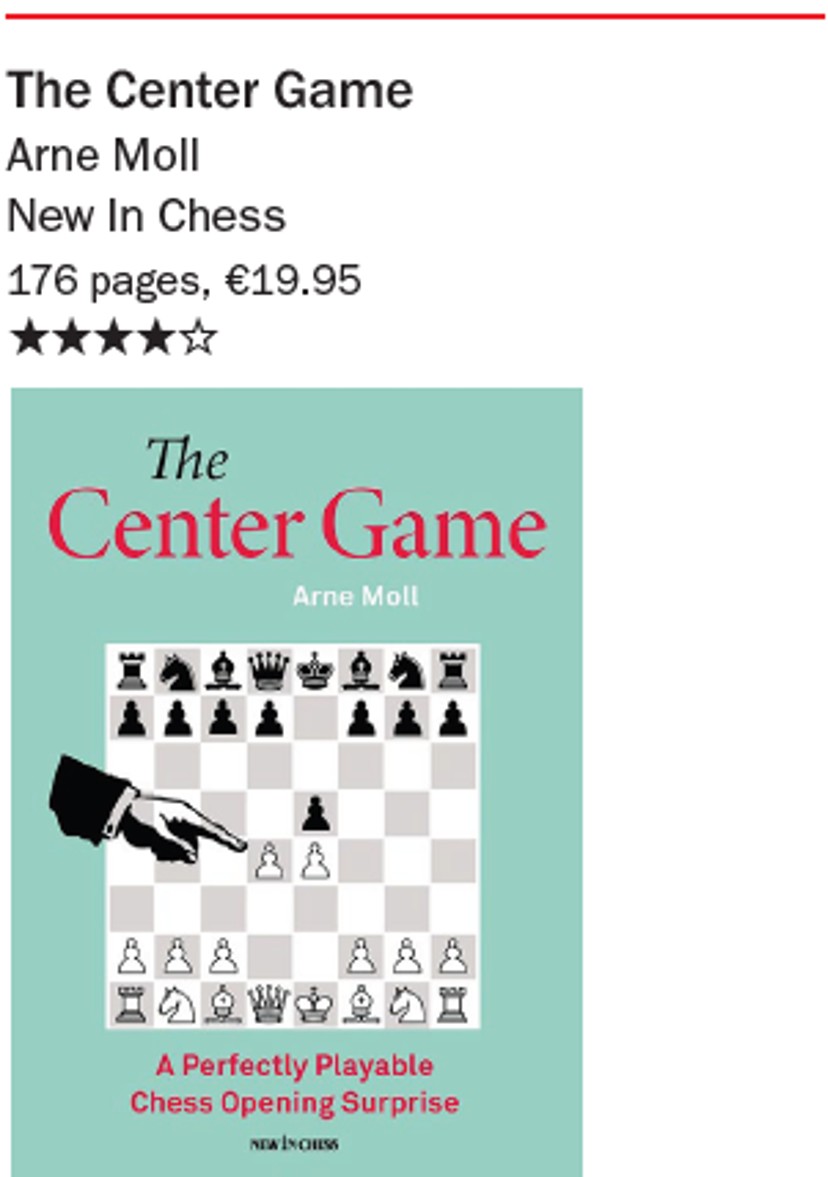

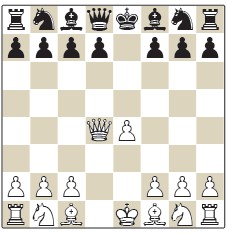

We finish up with two opening books to boost your White scoring (maybe) in 2025. Play the Mackenzie! by David Gertler and The Center Game by Arne Moll. We start with Play the Mackenzie! What is the Mackenzie you may ask? I didn’t know the name either but it’s this variation in the Ruy Lopez.

We finish up with two opening books to boost your White scoring (maybe) in 2025. Play the Mackenzie! by David Gertler and The Center Game by Arne Moll. We start with Play the Mackenzie! What is the Mackenzie you may ask? I didn’t know the name either but it’s this variation in the Ruy Lopez.

1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗b5 a6 4.♗a4 ♘f6 5.d4 For those already worrying that all they ever get nowadays is the Berlin Defence 3...♘f6, then don’t be afraid: Gertler also provides a chapter on the Mackenzie-style 4.d4 against it!

For those already worrying that all they ever get nowadays is the Berlin Defence 3...♘f6, then don’t be afraid: Gertler also provides a chapter on the Mackenzie-style 4.d4 against it!

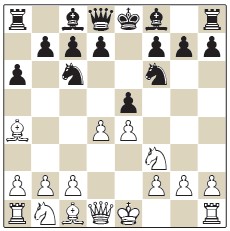

The move is named after the 19th century Scottish-born American master George Henry Mackenzie whose record in the database with it is pretty impressive: 11 wins and 5 draws! I feel that we are reaching the point with opening books where we no longer need to pretend that a White repertoire is winning in all lines. The emphasis is turning towards accepting that some lines are just equal (or even risk being slightly worse for White as in the Center Game!) but also stressing the difficulty for the opponent of finding the best lines unprepared and highlighting the practical merits of the lines recommended. Both books do this quite nicely in fact. In the case of the Mackenzie, one of the nicest motifs is the idea of sacrificing the lightsquared bishop and bringing the king’s knight quickly to f5 as in this line.

1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗b5 a6 4.♗a4 ♘f6 5.d4 exd4 6.0-0 ♗e7 7.e5 ♘e4 8.♘xd4 ♘c5 9.♘f5 This is surprising enough to cause a few heart palpitations in an unprepared player! A slim volume of 107 pages does a nice job of laying the groundwork for this system: 3 stars!

This is surprising enough to cause a few heart palpitations in an unprepared player! A slim volume of 107 pages does a nice job of laying the groundwork for this system: 3 stars!

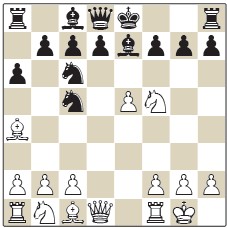

Now on to The Center Game. I got interested in the Center Game because I noticed that the Leela Knight Odds bot on Lichess was playing it quite frequently so I was intrigued to see what the opening looked like with an extra knight! What is the Center Game? It’s 1.e4 e5 2.d4, with the normal continuation 2...exd4 3.♕xd4.

Now on to The Center Game. I got interested in the Center Game because I noticed that the Leela Knight Odds bot on Lichess was playing it quite frequently so I was intrigued to see what the opening looked like with an extra knight! What is the Center Game? It’s 1.e4 e5 2.d4, with the normal continuation 2...exd4 3.♕xd4. This 172-page book is actually something between a history lesson and a theoretical manual, as the first two chapters are dedicated to the history of the Center Game and the last 100 pages focus on its theory. I’m not a fan of introductions with historical games – they often serve as fillers rather than adding anything new – but in this case, I will make an exception! When Stamma, analysing in 1745, recommends a counter for Black that is still popular today – 3...♘c6 4.♕e3 g6!? – then it’s definitely worthy of attention!

This 172-page book is actually something between a history lesson and a theoretical manual, as the first two chapters are dedicated to the history of the Center Game and the last 100 pages focus on its theory. I’m not a fan of introductions with historical games – they often serve as fillers rather than adding anything new – but in this case, I will make an exception! When Stamma, analysing in 1745, recommends a counter for Black that is still popular today – 3...♘c6 4.♕e3 g6!? – then it’s definitely worthy of attention!

Moll does a really good job of weaving historical development with modern practice and it is fascinating to see the development of the line and to understand where we have ended up today! You understand better why Moll also devotes a chapter to modern 4th move alternatives after 3...♘c6 – 4.♕a4, 4.♕c4 and 4.♕d3 – and why modern players are exploring these.

All-in-all, it was a very pleasant and entertaining read, somewhere between 3 and 4 stars but we’ll bump it up to 4 to start the year on a positive note! ■