These book reviews by Matthew Sadler were published in New In Chess magazine 2024#4

Three excellent books about Simen Agdestein, Mark Dvoretsky and Bobby Fischer each contained some amazing stories.

by Matthew Sadler

One of the things that struck me when I started work after my professional chess career was how little energy I needed to work at a decent level compared to chess. Anything less than eight hours’ sleep and a chess disaster was looming, whereas I’ve worked off four hours’ sleep for most of my (single) life and rarely felt the effects. Even with plenty of rest, by the time I’d got halfway through a classical tournament, I could feel myself retreating into a narrow, ‘programmed’ state where I was capable of doing everything related to chess but nothing else. At a certain moment during a tournament, I couldn’t read novels anymore (tiredness made me too sensitive to bad things happening to the characters) and I became quite vulnerable to the effect of negative comments (which led me to minimise outside contact as much as possible). Work has been extremely busy for the past few months and I’ve noticed a form of this ‘programmed’ state returning.

I mention this because I was mildly confused this month by my reactions to the books I reviewed. The books I thought I would love were less enjoyable than expected, while the books I assumed would be less interesting turned out to be very pleasurable!

Might be something to do with my current mood so please bear that in mind!

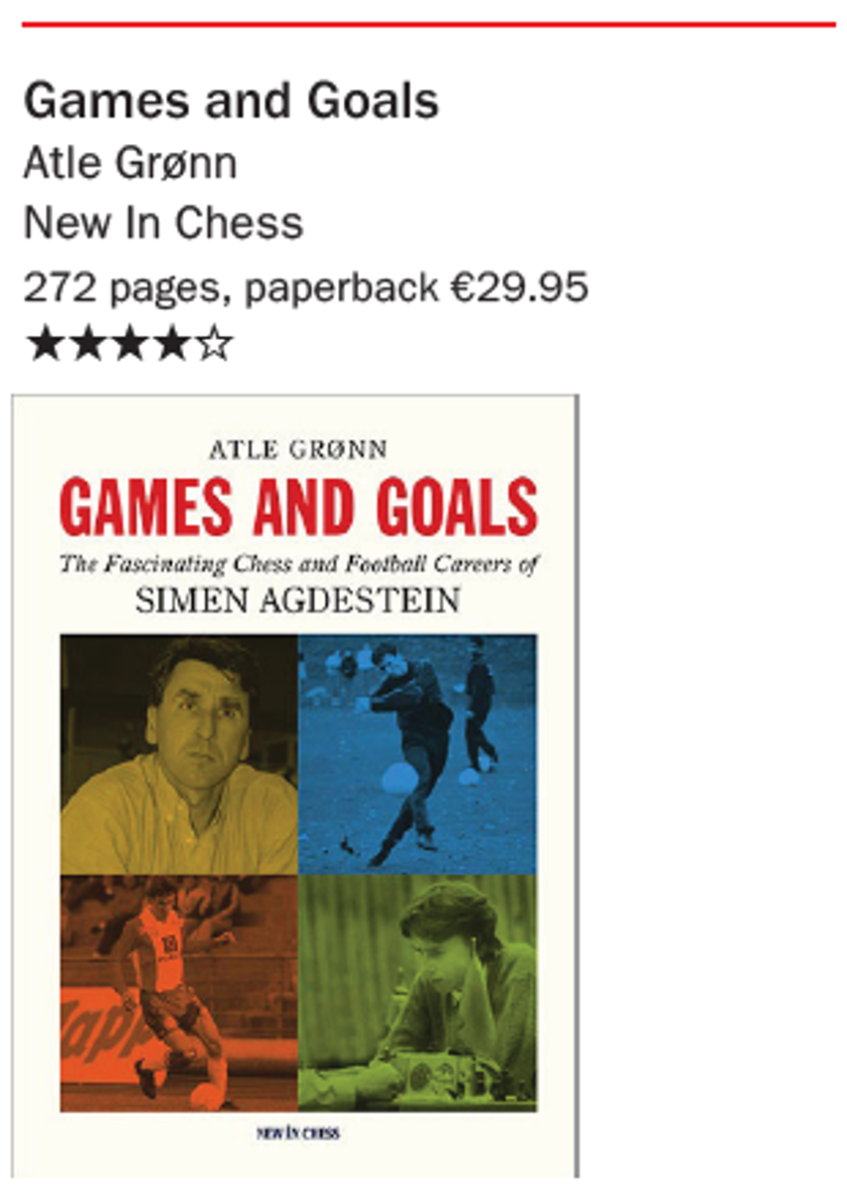

Games and Goals by Atle Grønn details in 272 pages and 38 photographs the life of the remarkable Norwegian grandmaster Simen Agdestein. Agdestein not only played chess at the elite level in the late 1980s and early 1990s, he also represented Norway multiple times at football in international competition. As a chess coach, he was responsible for fostering the talent of Magnus Carlsen and maintained his own chess strength to such an extent that he was able to win the Norwegian Championship in 2023 at the age of 56. The publication of this book is accompanied by two excellent interviews by Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam for the New In Chess podcast – one with the author Atle Grønn (a close friend of Agdestein’s) – and one with Simen Agdestein himself. I can thoroughly recommend listening to both!

Games and Goals by Atle Grønn details in 272 pages and 38 photographs the life of the remarkable Norwegian grandmaster Simen Agdestein. Agdestein not only played chess at the elite level in the late 1980s and early 1990s, he also represented Norway multiple times at football in international competition. As a chess coach, he was responsible for fostering the talent of Magnus Carlsen and maintained his own chess strength to such an extent that he was able to win the Norwegian Championship in 2023 at the age of 56. The publication of this book is accompanied by two excellent interviews by Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam for the New In Chess podcast – one with the author Atle Grønn (a close friend of Agdestein’s) – and one with Simen Agdestein himself. I can thoroughly recommend listening to both!

Agdestein sharply curtailed his chess activities as I started my professional career so I never really came across him, although I was obviously familiar both with his name and his results. It didn’t really register with me at the time that he was barely playing, especially as his rare outings seemed to show an undiminished chess strength: for example, a 2-2 draw against Michael Adams in a 1994 match in Oslo! The book takes us through Agdestein’s early years, steps off to consider his maternal and paternal inheritance and then takes us through the surprisingly lively Norwegian chess scene to his first encounters with the world elite. One thing that amazed me frequently while reading was how quickly things happened for him. At some stage you read a sentence ‘Could a 21-year-old be bought?’ and you have to flick back a few pages to truly believe that he had come so far while barely in his twenties!

Perhaps the most shocking part of the book was to read about the profound effect of the football injuries – that eventually ended his football career – on his life and how difficult he found things in the aftermath. I was vaguely aware at the time hat he had been forced to stop with football but remembered blithely thinking that he would simply play chess instead, since he was lucky enough to be so good at both! Life is, however, much more complicated than that – even for those who excel in many things – and it took some years before he regained his purpose and focus.

I enjoyed many aspects of this book. Grønn – somewhat by coincidence as we learn during his interview – was granted access to Agdestein’s diary and letters and this gives us some raw and personal insights into Agdestein’s thinking at the time which are very unusual for a chess book. The book even begins with a striking quote which he confided to his diary in 1987: ‘I know I am one of the greatest chess talents in history. I was born special and I have to learn to live with, accept that. I am the one chosen to sacrifice for – and be sacrificed to – chess.’ Followed by another one from just two months later: ‘I hereby disclaim any responsibility for what I might write. I am so angry I could burst. You may not know what it means, but I have just lost on time in a winning position.’

which he confided to his diary in 1987: ‘I know I am one of the greatest chess talents in history. I was born special and I have to learn to live with, accept that. I am the one chosen to sacrifice for – and be sacrificed to – chess.’ Followed by another one from just two months later: ‘I hereby disclaim any responsibility for what I might write. I am so angry I could burst. You may not know what it means, but I have just lost on time in a winning position.’

And yet somehow, the book failed to captivate me completely which rather surprised me – I love biographies (of chess players, composers, artists etc...) and this was book was very well researched with a very interesting protagonist.

I thought a lot about what was lacking for me, but it only struck me when comparing it to Paul van der Sterren’s autobiography In Black and White, which I loved unreservedly. In Black and White was fundamentally a joyous book. There was loneliness and stress, there were terrible lows and tragic blunders, but the redemptive power of a well-played chess game to uplift you and make you see life in bright colours once more infused his writing.

I couldn’t have survived my short professional career without the occasional game that left me humming to myself with pleasure for weeks! Without that, chess competition is only attritional and often cruel. I really missed this quality in Games and Goals, to the point where I even found it a little distressing. Perhaps that’s a consequence of Grønn’s conscious structuring of the book, which places a selection of lightly-annotated games in an appendix and limits chess content in the main part of the book to single diagrams. This nicely avoids interrupting the flow of the text with chess content; on the other hand, it perhaps relegates the drama of the chess itself to a too-insignificant role.

This is quite a personal take and I would unreservedly recommend you to decide for yourselves whether you agree! An excellent book combined with two superb podcast interviews: 4 stars from me!

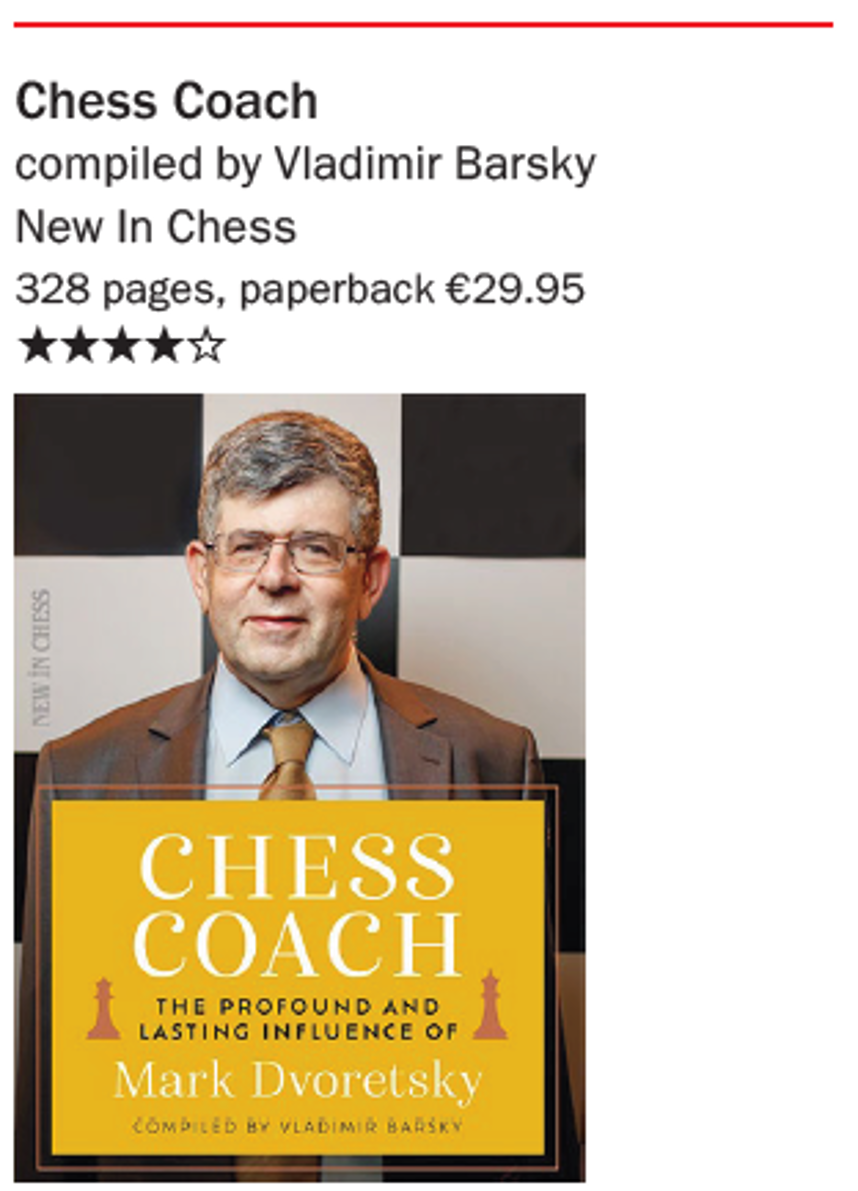

Chess Coach, compiled by Vladimir Barsky, is a 324-page tribute to the much-missed Russian coach Mark Dvoretsky. The first part of the book is a compilation of reminiscences about the great man by students and contemporaries starting with no less than Garry Kasparov and ending quite movingly with memories from his wife and son. The second part is a compilation of Dvoretsky’s best games, annotated by his pupils (not the weakest annotators, as you can imagine!), followed by a whole section dedicated to Dvoretsky’s love of studies. The final section compiles interviews with Dvoretsky from various sources.

Chess Coach, compiled by Vladimir Barsky, is a 324-page tribute to the much-missed Russian coach Mark Dvoretsky. The first part of the book is a compilation of reminiscences about the great man by students and contemporaries starting with no less than Garry Kasparov and ending quite movingly with memories from his wife and son. The second part is a compilation of Dvoretsky’s best games, annotated by his pupils (not the weakest annotators, as you can imagine!), followed by a whole section dedicated to Dvoretsky’s love of studies. The final section compiles interviews with Dvoretsky from various sources. It’s a book that is simply very pleasant to browse through, as there is always something unfamiliar and interesting waiting for you on the next page! This game against the great Paul Keres played in a match-tournament in 1973 (Dvoretsky was on the youth team) is a lovely example!

It’s a book that is simply very pleasant to browse through, as there is always something unfamiliar and interesting waiting for you on the next page! This game against the great Paul Keres played in a match-tournament in 1973 (Dvoretsky was on the youth team) is a lovely example!

Paul Keres

Mark Dvoretsky

Moscow 1973

French Defence, Tarrasch Variation

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.♘d2 ♘f6 4.♗d3 c5 5.e5 ♘fd7 6.c3 b6 7.♘e2 ♗a6 8.♗xa6 ♘xa6 9.0-0 ♘c7

This game is annotated by Vadim Zviagintsev, one of Dvoretsky’s favourite pupils. He notes that ‘Black can follow one of two plans. The first is to close the centre with ...c5-c4 and then play ...b6-b5-b4, but this is quite slow and not very dangerous for White. The second and more logical approach is to prepare ...f7-f5 or ...f7-f6. With this aim, the knight defends the e6-pawn.’

10.♘f4 ♗e7 11.♖e1

‘By bringing the rook to the e-file, White prevents his opponent’s plan.’

11...0-0 12.♘f1 ♕c8 ‘From this moment, Dvoretsky starts to defend extremely inventively. 12...♕c8 is a very important move, ‘mysterious’ in Nimzowitsch’s terminology. What does Black want? He intends to play ...f7-f5 and after the exchange to recapture on e6 with the knight when the e6-pawn will be defended additionally by the queen. Then he will play ...♗d6 and stand normally.’

‘From this moment, Dvoretsky starts to defend extremely inventively. 12...♕c8 is a very important move, ‘mysterious’ in Nimzowitsch’s terminology. What does Black want? He intends to play ...f7-f5 and after the exchange to recapture on e6 with the knight when the e6-pawn will be defended additionally by the queen. Then he will play ...♗d6 and stand normally.’

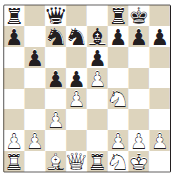

13.♘g3 f5 14.c4 g5 15.♘xe6

15.♘xe6

Fifteen moves into a sleepy French, the whole board is on fire!

15...♘xe6 16.cxd5 ♘xd4 17.d6 ♗d8 18.e6

‘White not only has two dangerous passed pawns in the centre, but also splendid attacking chances, because the king on g8 is very weak. Now we see the start of a series of brilliant defensive moves from Black.’

‘White not only has two dangerous passed pawns in the centre, but also splendid attacking chances, because the king on g8 is very weak. Now we see the start of a series of brilliant defensive moves from Black.’

18...♗f6 19.♘h5

White wants to exchange the bishop on f6 and win the g5-pawn.

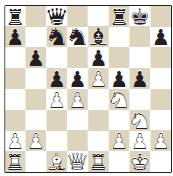

19...♕c6 20.exd7 ♕xd6 21.♘xf6+ ♕xf6 22.♗e3 ♖ad8 23.♕a4 ♕d6 24.♗xg5 ♖xd7 25.♗e3

25.♗e3

‘Evidently Keres came to the conclusion that he had no advantage and it was necessary to force the draw. But after 25.♗f4 ♕c6 26.♕c4+ ♕d5 27.♕xd5+ ♖xd5 28.♖e3 the ending is more pleasant for White.’

25...f4 26.♗xd4 ♕xd4 27.♕xd4 ♖xd4 28.♖e2 f3 29.gxf3 ♖xf3 30.♖ae1 ♔g7

Draw.

A varied and engaging book. It’s somewhere between three and four stars for me but we’ll bump it up to four!

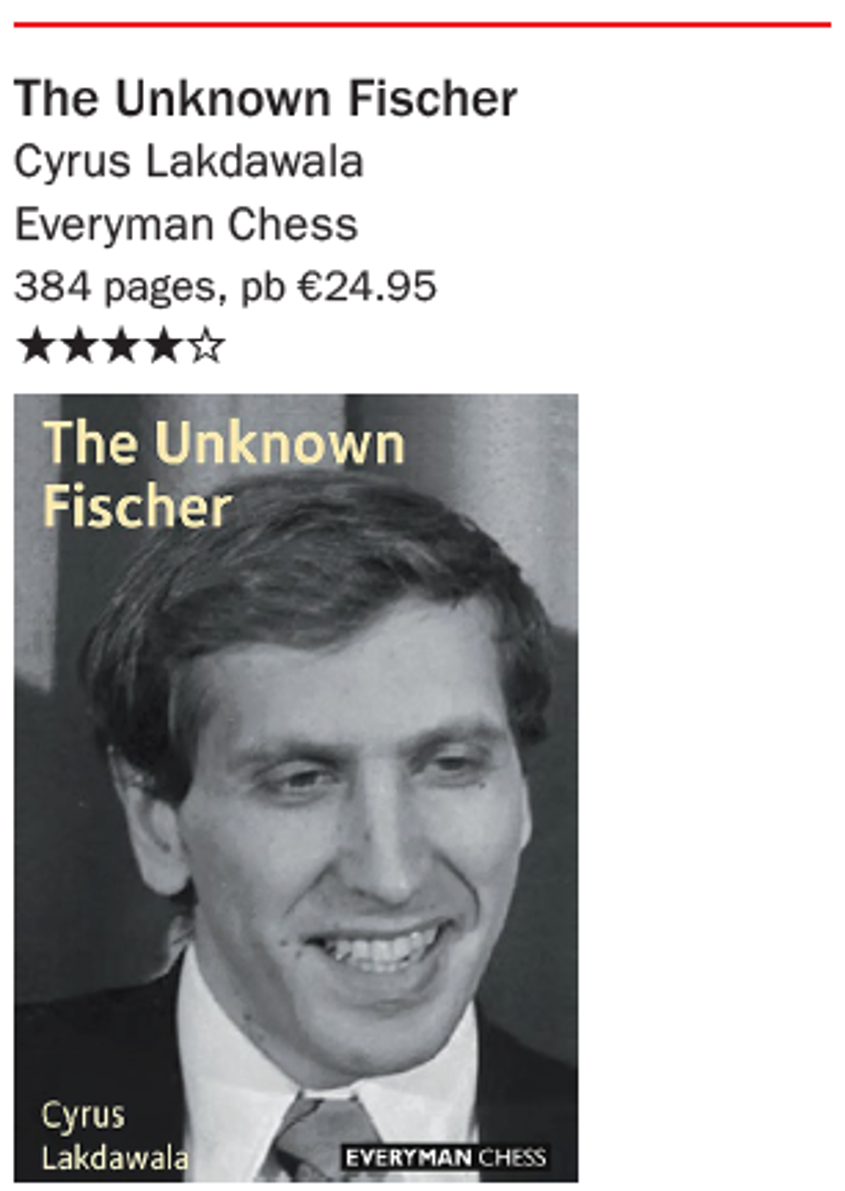

I did a double-take when I saw the title The Unknown Fischer by Cyrus Lakdawala. Surely that title had already been used? Not quite in fact, since the book I was thinking of was The Unknown Bobby Fischer by John Donaldson and Eric Tangborn (notable for a really nice photo on the cover of a young, smiling Bobby playing chess). I gave a little inward sigh as I opened the parcel of books that had just arrived, as I unfortunately tend to do when I see a new book about Fischer. I’m not sure why, as I admire Fischer’s play enormously. I guess it’s partly due to the fact that I was born after the Fischer hype had subsided.

I did a double-take when I saw the title The Unknown Fischer by Cyrus Lakdawala. Surely that title had already been used? Not quite in fact, since the book I was thinking of was The Unknown Bobby Fischer by John Donaldson and Eric Tangborn (notable for a really nice photo on the cover of a young, smiling Bobby playing chess). I gave a little inward sigh as I opened the parcel of books that had just arrived, as I unfortunately tend to do when I see a new book about Fischer. I’m not sure why, as I admire Fischer’s play enormously. I guess it’s partly due to the fact that I was born after the Fischer hype had subsided.

The gods when I started in chess were first Karpov and then Kasparov and my nine-year-old self didn’t consider the man who had ducked the challenge of facing Karpov to be worthy of any attention! (You can be pretty harsh at that age!) Somehow, those first impressions have a way of stretching into adult life. I also wondered how much more could usefully be said about Fischer after all the books that have appeared about him, especially considering his short playing career.

Well, I was once again pleasantly surprised! Lakdawala selects 80 games to annotate, of which only a few were familiar to me. He starts with two youthful losses (in a chapter entitled ‘Bobby’s Early Goof-Ups’), before moving on to a variety of games from various sources, many of which are from Fischer’s earlier years.

The last four chapters are the most exotic, with serious attention devoted to games from simultaneous displays, 1977 games against the (rather weak) MacHack VI chess computer, blitz games and the training match that Fischer played against Svetozar Gligoric (winning 7½-2½ against the veteran) before his 1992 rematch against Boris Spassky. This selection of games by Lakdawala works really well. The games from Fischer’s younger years are quite striking: less controlled and more overtly attacking than the machine-like efficiency we saw in Fischer’s best years.

I lost count of the number of times Lakdawala highlighted the aggressive thrust g4! in Fischer’s early games! A serious analysis of Fischer’s blitz games at the Herceg Novi 1970 blitz tournament (which Fischer won with 19/22, 4½ points ahead of a star-studded field) also raises some interesting thoughts. Lakdawala suggests very bravely that ‘[Bobby’s blitz] play was nowhere near present-day top players’ blitz abilities, that of Magnus, Nepo, Ding and Hikaru’, and it’s hard to disagree, although there are definitely some wonderful games in there, such as Fischer’s two wins against Petrosian and a totally bananas draw against Bronstein.

A serious analysis of Fischer’s blitz games at the Herceg Novi 1970 blitz tournament (which Fischer won with 19/22, 4½ points ahead of a star-studded field) also raises some interesting thoughts. Lakdawala suggests very bravely that ‘[Bobby’s blitz] play was nowhere near present-day top players’ blitz abilities, that of Magnus, Nepo, Ding and Hikaru’, and it’s hard to disagree, although there are definitely some wonderful games in there, such as Fischer’s two wins against Petrosian and a totally bananas draw against Bronstein.

The match against Gligoric produced my favourite games of the book. I wasn’t aware this match had even taken place and it featured some interesting theoretical discussions in the Zaitsev Ruy Lopez (when Fischer was White) and the Classical King’s Indian (when Fischer was Black). Fischer also did a couple of odd things during the match. The following zany opening was his one flirtation with something other than 1.e4:

Bobby Fischer

Svetozar Gligoric

Sveti Stefan training match 1992

English Opening

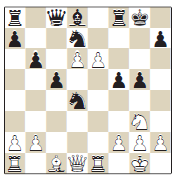

1.c4 c5 2.b3 ♘c6 3.g3 ♘f6 4.♗g2 d5 5.cxd5 ♘xd5 6.f4 e6 7.♗b2 h5 8.♘h3!? ♘f6 9.♘f2!? h4!? 10.♘c3 hxg3 It wasn’t particularly successful (though Fischer won the game in the end), and Lakdawala draws an interesting parallel with a blitz game of Fischer’s against Vaslily Smyslov that was played in Herceg Novi in 1970.

It wasn’t particularly successful (though Fischer won the game in the end), and Lakdawala draws an interesting parallel with a blitz game of Fischer’s against Vaslily Smyslov that was played in Herceg Novi in 1970.

Bobby Fischer

Vassily Smyslov

Herceg Novi blitz 1970

Bird’s Opening 1.f4

1.f4 d5 2.♘f3 ♘f6 3.b3 g6 4.♗b2 ♗g7 5.g3 Fischer also tried this peculiar Queen’s Indian structure twice that looks like something out of the 1920s. You really wonder what might have attracted him to it:

Fischer also tried this peculiar Queen’s Indian structure twice that looks like something out of the 1920s. You really wonder what might have attracted him to it:

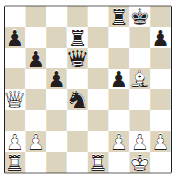

Svetozar Gligoric

Bobby Fischer

Sveti Stefan training match 1992

Queen’s Indian Defence

1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 e6 3.♘f3 b6 4.♘c3 ♗b7 5.e3 ♘e4 6.♗d3 ♘xc3 7.bxc3 ♗e7 8.e4 d6 9.0-0 0-0 10.♗e3 Gligoric enjoyed himself quite a bit on the White side, as you can imagine!

Gligoric enjoyed himself quite a bit on the White side, as you can imagine!

All-in-all, a welcome exploration of some lesser-known Fischer games. I certainly felt I learned a lot about his play! Four stars!